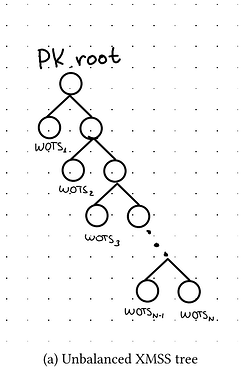

Abstract: Stateful hash-based signature schemes can be very efficient when the number of signatures generated by a public key is small. One major problem with stateful schemes is that the state needs to be backed up and updated correctly after every signing operation. By using a straightforward combination of a stateless hash-based scheme (such as a variant of SPHINCS+) and an unbalanced XMSS tree of one-time signatures (stateful), we obtain a scheme that we call SHRINCS. It is extremely efficient when only a few signatures are required and can be backed up with a static seed. More precisely, the SHRINCS public key is a hash of the stateful and stateless public keys. We assume key generation happens on a signing device that is able to keep state securely. Therefore, the signing device can use efficient stateful signatures to sign for the public key. When the state is known to be corrupted or lost, for example when a static seed backup has been restored, the signing device only uses stateless signatures. As a result, SHRINCS provides the efficiency of stateful signatures during normal operation while maintaining the robustness of stateless signatures as a fallback.

SHRINCS

SHRINCS is briefly covered deep in the appendix of our report “Hash-based Signatures for Bitcoin” (Hash-based Signature Schemes for Bitcoin) by Mikhail Kudinov and myself. This post gives a fuller explanation and invites feedback.

The construction of SHRINCS requires a stateless signature scheme and a stateful signature scheme that generates small signatures. SHRINCS consists of the following algorithms:

- \textsf{KeyGen}() \rightarrow (\mathit{seed}, \mathit{pk}, \mathit{state}): The keygen algorithm draws a master seed, derives secret keys \mathit{sk}_1 and \mathit{sk}_2 for the stateful and stateless signature schemes, respectively. Using these, it generates public keys \mathit{pk}_1 and \mathit{pk}_2 for the stateful and stateless schemes. Finally, \textsf{KeyGen} returns the tuple (\mathit{seed}, \mathit{pk}, \mathit{state}) where \mathit{pk} = H(\mathit{pk}_1, \mathit{pk}_2) and \mathit{state} is the initial state of the stateful scheme.

- \textsf{Restore}(\mathit{seed}) \rightarrow (\mathit{seed}, \mathit{pk}, \mathit{state}): The restore algorithm rederives the SHRINCS public key \mathit{pk}, sets \mathit{state} to \textsf{LOST} and returns the tuple (\mathit{seed}, \mathit{pk}, \mathit{state}).

- \textsf{Sign}(\mathit{seed}, \mathit{state}, m) \rightarrow (\mathit{state}', \mathit{sig}): If \mathit{state} \neq \textsf{LOST}, the signing algorithm rederives \mathit{sk}_1 and \mathit{pk}_2 and runs the \textsf{Sign} algorithm of the stateful scheme with \mathit{sk}_1, \mathit{state} and message m. Then, it returns the updated state \mathit{state}' along with the signature concatenated with \mathit{pk}_2. Otherwise, the signing algorithm rederives \mathit{sk}_2 and \mathit{pk}_1, runs the \textsf{Sign} algorithm of the stateless scheme with \mathit{sk}_2 and m, and returns \mathit{state}' = \mathit{state} and the signature concatenated with \mathit{pk}_1.

- \textsf{Verify}(\mathit{pk}, m, \mathit{sig}) \rightarrow \{\textsf{true}, \textsf{false}\}: The verification algorithm parses \mathit{sig} as \mathit{sig}' \| \mathit{pk}', verifies \mathit{sig}' according to the stateless or stateful scheme (which recovers the signing public key in hash-based schemes), and checks that the two public keys hash to \mathit{pk}.

So, when a signing device capable of maintaining state securely is initialized, it signs with the stateful scheme, but whenever a device is restored with the seed, it only signs with the stateless scheme. Because the stateful path is much more efficient in SHRINCS, signing from a restored device is much more expensive than from the device that originally ran \textsf{KeyGen}.

For the stateless signature scheme in SHRINCS, candidates include SLH-DSA or one of the variants of SPHINCS+ that we cover in detail in the report. Depending on the parameters, signature size is between 3KB and 8KB and the public key is 16 bytes (at NIST security level 1). For the stateful scheme SHRINCS uses what we call “unbalanced XMSS”. A regular XMSS public key is essentially a Merkle tree of one-time signature (OTS) public keys. A one-time signature scheme can generate no more than a single signature for a public key, otherwise it becomes insecure. So, the signing state is just the number of signatures that have already been produced, initialized at q=0. To sign a message in XMSS, the signer increments q, produces a signature with the q-th one-time public key in the Merkle tree, and computes the authentication path (aka “Merkle proof”) to the root. The final signature is essentially the one-time signature concatenated with the authentication path.

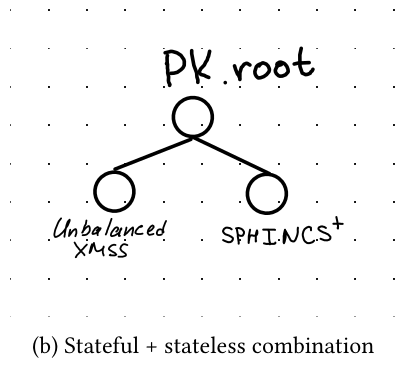

Instead of using a balanced Merkle tree of OTSs, we use an unbalanced tree for the stateful part of SHRINCS. Thus, the first OTS is at depth 1, the second OTS at depth 2 and so on. This minimizes authentication path length for early signatures, which is optimal when few signatures are expected. The q-th signature for this “unbalanced XMSS” scheme is the q-th OTS signature and its authentication path. At NIST security level 1, the size of the authentication path is q \cdot 16 bytes and the size of the OTS signature is 292 bytes. More precisely, for the OTS we use WOTS+C (for details, check the paper).

Putting it all together, when signing with intact state, the signature size of SHRINCS is \min(292 + q \cdot 16, s_l) + 16 where q is the number of signatures that have been generated for the public key through the stateful path and s_l is the size of signatures generated with the stateless scheme. For q = 1 this signature is more than 11x smaller than the smallest NIST-standardized scheme (ML-DSA). I’d expect that average q for regular Bitcoin wallets is between 1 and 2. The main downside of SHRINCS remains that security requires secure state management. However, unlike pure stateful schemes where state mismanagement can be catastrophic, if in doubt, SHRINCS signers can always fall back to the stateless path.