I’d like to share some of my recent node traffic analyses in case someone else might find the method for making estimates estimates or some of the insights enabled by the estimates useful.

I initially did this work to figure out what kind of bandwidth savings to expect for Erlay, but I think the approach and data might be useful for other P2P optimizations as well.

While measuring overall node traffic is trivial (e.g., via iptables,

systemd’s IP accounting), there’s hardly anything useful to learn from it. In need of a useful traffic breakdowns through various lenses, I decided to

try to estimate TCP/IP traffic using data collected via the the

net:inbound_message

and net:outbound_message

tracepoints.

Here’s how it works. Based on payload sizes reported by the tracepoints, the P2P message size is computed by adding the P2P message overhead (24 bytes, made up up a 4-byte magic, 12-byte command, and 4-byte each for payload length and checksum). Next, the number of TCP segments required to transmit the message is estimated by dividing the the P2P message size by the TCP segment size, where the TCP segment size is estimated to be the difference between the maximum transfer unit (MTU), which was assumed to be 1500 bytes, and the sum of the IP and TCP header sizes, the former of which was assumed to be 20 bytes in case of IPv4 and 40 bytes in case of IPv6 and the latter to be 32 bytes (made up of the default TCP header size of 20 bytes plus a ten-byte timestamp used by default by the Linux kernel to make real-time round-trip measurements plus two padding bytes to make the TCP header options to align to 32-bit boundaries). Next, the TCP/IP header overhead is computed by multiplying the number of TCP segments by the header overhead (which is the sum of IP and TCP headers). Also, since since ACKs are generally sent for every two TCP packets, the ACK overhead is estimated to be half the number of TCP segments times the sum of IP plus TCP header sizes. The final TCP/IP traffic estimate then corresponds to the sum of the P2P message size, the TCP/IP header overhead and the ACK overhead.

While all of this might sound rather convoluted to someone unfamiliar with the TCP/IP stack, it’s actually a first-principles-based analytic estimate.

Let’s have a look at some data to get an idea of the accuracy of traffic estimates made that way.

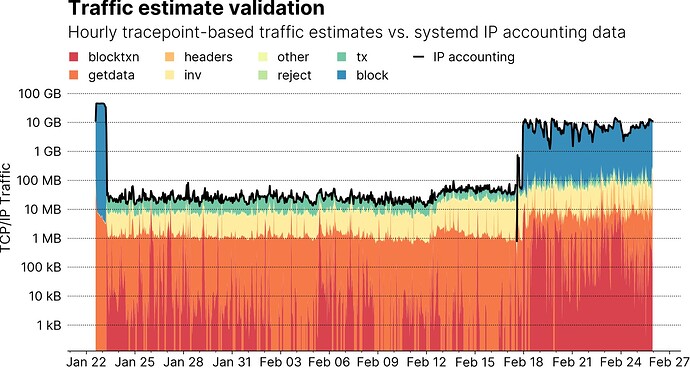

The graph below shows tracepoint-based hourly traffic estimates for different P2P message types (types with negligible amount of traffic have been grouped into the other category) over time. Individual message types are stacked on top of each other so they should add up to total node traffic. For validation, the black line shows total node traffic as reported by systemd’s IP accounting. Note that during the time data was recorded, the node underwent four different modes of operations, which are accompanied by significant changes in hourly bandwidth, so the graph uses a log-scale on the y-axis to make the data readable:

- During the first couple of hours, you can see tens of GB of block messages, which of course correspond to IBD.

- Afterwards, when hourly traffic drops to tens of MB per hour, the node was running for a couple of weeks without being reachable until around Feb 12.

- From Feb 12 to Feb 18, the node was made reachable, but was run in pruned mode, and traffic increases slightly, because the number of peer connection increases by an order of magnitude due to inbound connections.

- Finally, I attached a disk from a non-pruned node and disabled pruning on the node under observation as well. The upshot being that peers could now involve my node during their IBD, cause total node traffic to surge to ~10GB per hour.

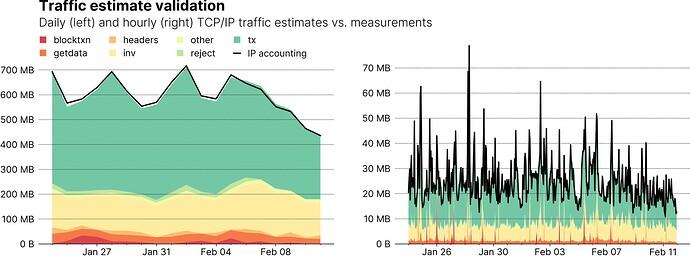

Looking at the data, one might get the feeling that the stacked estimates and the measurement (black line) are in very good agreement all of the time. But a log-scale graph is a bad way to judge the agreement visually, so the next two graphs use a linear y-axis scale, and focus on the time the node was not reachable, making it much easier to judge the discrepancy between estimate and measurement. The graph on the left shows daily traffic, while the one on the right shows hourly data. In both cases, the average model error hovers at around 1% with a maximum error of around 2%. Good enough in my book.

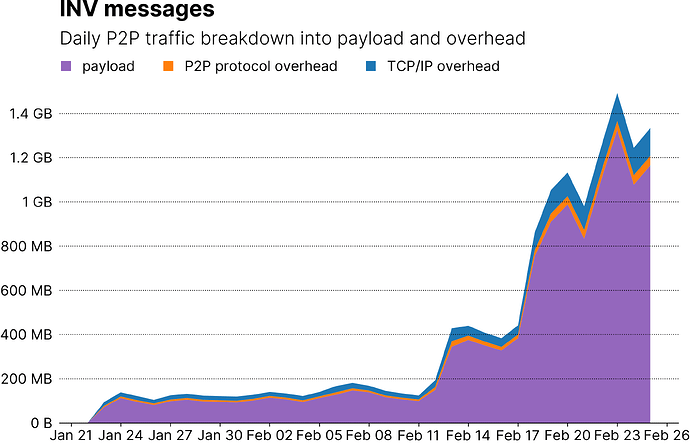

So, after demonstrating the method works, we can safely use its estimates for interpreting node traffic. For example, breaking down traffic by message type can help us assess potential optimizations. In the case of Erlay, I think it’s safe to say that there’s significant bandwidth-saving potential for non-listening (where daily INV traffic is more than 100MB out of a total of around 500-600MB) and pruned nodes; for listening nodes, where INV traffic rises by an order of magnitude but total node traffic is in the hundreds of GB per day: hardly gonna make a difference.

So, what else can you do with this approach other than breaking traffic down by message type? For one, you can break down traffic by payload (what’s in the P2P message) and overhead (e.g. the P2P message header overhead and TCP/IP overhead), which can be a useful tool to measure the impact of message buffer timer optimizations.

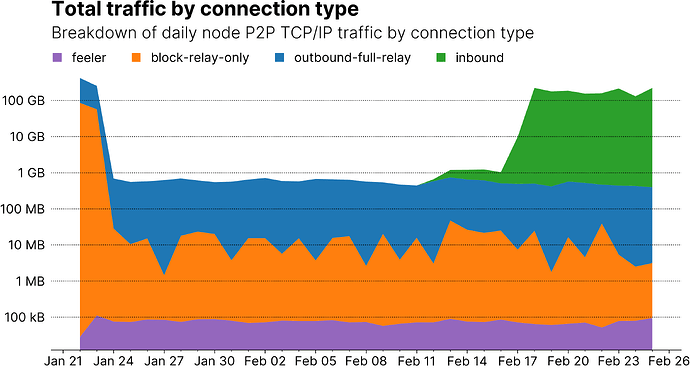

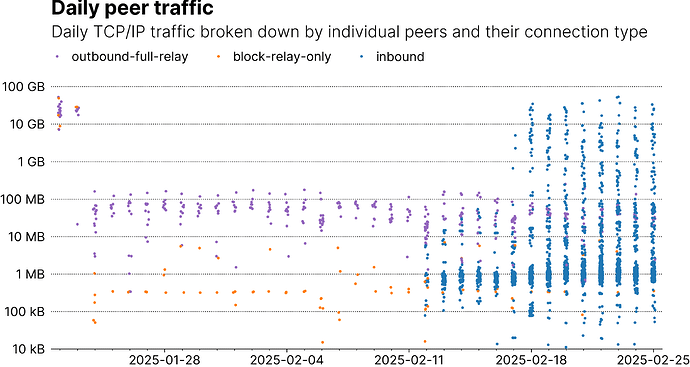

You can also break down traffic by connection types as shown in the graph below. Again, the graph shows the different stages the node was in during the time data was collected. During the first days, block data for IBD is received via both regular outbound and block-relay-only connections. After IBD, the traffic for all connection types stabilizes. After making the node reachable, but pruned, a small amount of traffic from incoming connections becomes visible (NB that it’s actually more traffic than the outbound connections because there’s many more inbound than outbound connections, but this is visually skewed by the log scale on the y axis). After disabling pruning, traffic by incoming connections grows significantly as peers start using my node for IBD. A breakdown such as this could be useful in verifying the impact of optimizations such as raising the number of block-only connections, which while significantly improving against eclipse attacks should not scale up traffic a lot.

Also, you can also break down per-peer traffic, which I found instructive to test and fill in some missing numbers of my mental models about overall P2P networks dynamics. In the plot below, each dot, color-coded by connection type, corresponds to the total TCP/IP traffic exchanged with a peer on a given day. Note that, since we might get disconnected by a peer at any moment and will then connect to a new one, there might be more dots in a connection type category than the number of slots for that type.

Unsurprisingly, we find both block-only and outbound connections with high traffic during IBD. When the node was bootstrapped but not reachable, we see traffic for both connection types drop and exhibit a level of stability that feels reasonable.

The first inbound connections appear on Feb 18. When pruning was disabled shortly before Feb 18, high-traffic incoming connections with more than 100MB of traffic being to appear.

I believe incoming nodes can be grouped into three categories: IBD nodes, regular nodes, and spy nodes.

- Regular nodes: My node’s outbound full relay connections (purple) are used for regular node maintenance (receiving INVs, TXs, BLOCKs, etc) and exhibit daily traffic between 10MB-100MB. Since my node’s outbound connections correspond to incoming connections on another node, incoming connections on my end that serve regular node maintenance should thus exhibit similar traffic patterns, which some of my node’s inbound connections do. Especially from Feb 12 to Feb 18, when my node was originally made reachable but running in pruned mode.

- IBD nodes: I think it’s safe to conclude that those incoming peer connections with more than 100MB of daily traffic correspond to nodes using my node for IBD, with the most obvious piece of evidence being that none of these high-traffic peers existed when my node was pruned.

- Spy nodes: Now interestingly, the bulk of inbound peers exchange only around 1MB of traffic with my node, which is too low (using traffic via my outbound connections as baseline) for them to be regular connections. All those nodes do is complete the P2P handshake, and politely reply to ping messages. Other than that, they just suck up our INV messages. Now one might argue these might be SPV nodes but they’re definitely not (the most obvious give away is that they never send any SPV-related messages; in fact, all they ever send is a single

VERSIONand a singleADDRmessage, as well asPONGs; the fact that they’re coming from a limited bunch of IPs or IP ranges doesn’t help)

If someone has any more ideas about useful data to generate, let me know and I’ll try to visualize it. If you want to play around yourself, I’ve put all of the Jupyter notebooks on GitHub. Unfortunately, raw tracepoint data was too big for GitHub but I’ve left some data that’s been grouped to hourly and daily resolution in the repo; if you want access to some raw tracepoint data, just let me know where to scp or ftp it.