Dear fellow Lightning developers,

at this time I believe I have rather strong evidence to explain how economic rational behavior and network topology lead to the high rate of channel depletion that we observe on the network.

Thus, I would like to share some follow up results of the mathematical theory of payment channel networks with you. Before extending the linked document I thought I collect feedback from you about two notebooks / results (notebook1 and notebook2) that I have been developing after your valuable thoughts and feedback in Tokyo.

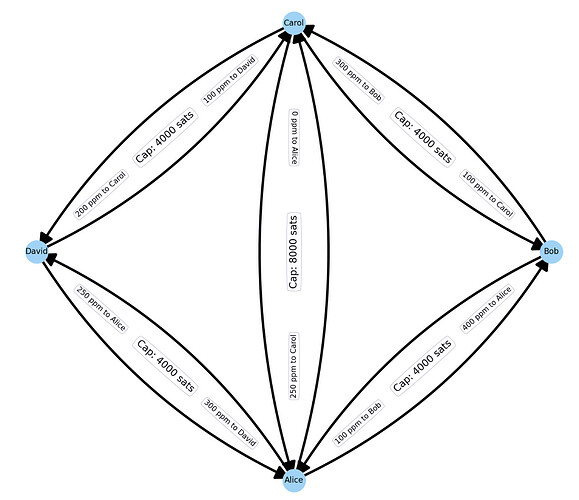

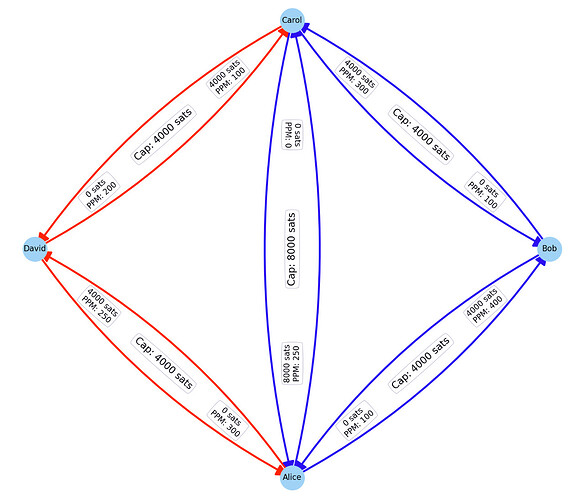

In the afore mentioned paper I already provided a proof for the intuitive observation that cycles on the channel graph produce several liquidity states with the same wealth distribution (as a cycle usually allows for circular off-chain rebalancing, which - when neglecting routing fees - does not change the wealth distribution. Similarly it was shown with a markov model that the steady state of the LN is a spanning tree while all other channels should be depleted. I am able to come to the same conclusion but with a different approach:

Fee Potential of the Network

(The motivation why to study the fee potential will follow in the next section)

Neglecting the base fee we can define the fee potential of a node as:

\phi_v = \sum_{e\in E: v\in E}\left(\lambda(v,e)\cdot ppm(v,e)\right)

This is just the sum of a node’s outgoing liquidity in all their channels multiplied with the ppm the node can expect to earn when routing the liquidity on the channel. This is motivated by note operators who seem to maximize their fee potential.

In a similar fashion the fee potential for the entire network can be defined as:

\phi = \sum_{v\in V}\phi_v

Using integer linear programming when finding a feasible liquidity state for a given wealth distribution one could at the same time find a feasible liquidity state that maximizes \phi (or more conveniently minimize -\phi). I have done this in this notebook and made a rather interesting observation:

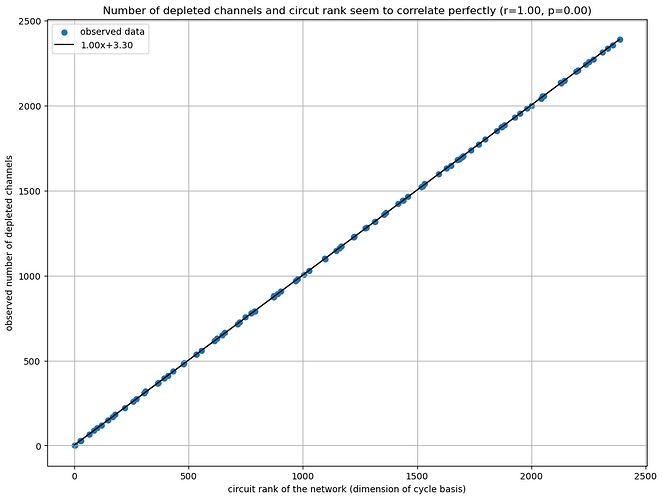

We see that the number of depleted channels in the network grows linearly with the circuit rank of the network when \phi is being maximized. Working over 10 years in statistics this is the strongest correlation on emperical data that I have ever seen. So it will be no surprise that I have a formal proof for this pattern to occur. (Disclaimer: Sidiropoulos shared a similar proof with me in a private conversation after I showed him the diagram / result).

(The circuit rank basically tells us how many more channels we have than a spanning tree or hub and spoke model.)

Why maximizing the fee potential?

Now you could argue why should the network coordinate to maximize \phi? I was doing the same. Thus I created a small simulation in a second notebook to study if the default behavior of nodes would produce a similar state as globally solving the optimization problem.

For this I assumed the network to be initially in a random state and that nodes send each other money. For sending money the agents in the simulation will use liquid payment routs that minimize their cost. Without loss of generality I choose just the ppm as a cost function for the min cost flow computation.

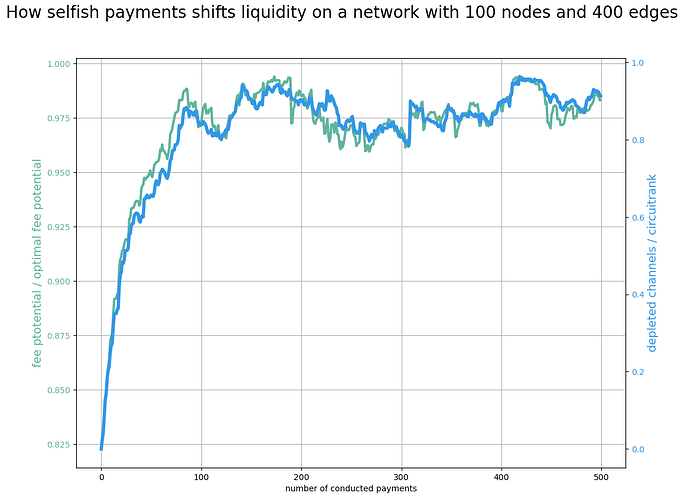

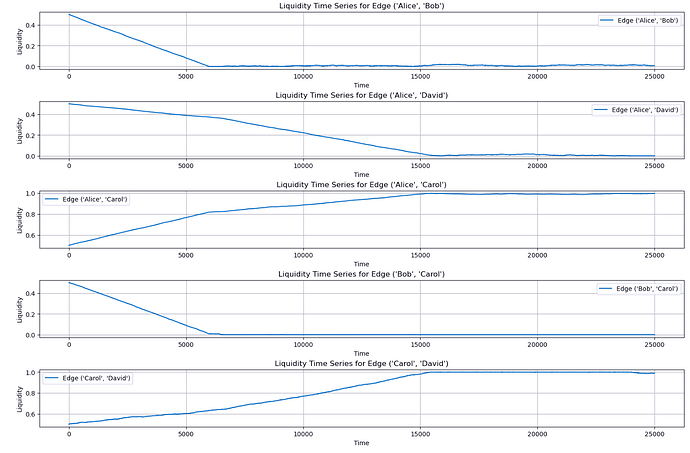

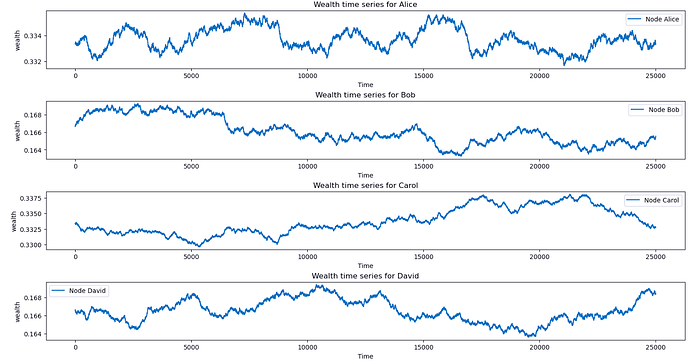

After every simulation step I computed the networks fee potential \phi and compare it with the maximized \phi potential. Similarly I looked how many channels are depleted and compared it with the circuit rank of the network.

One can see that very quickly the network reaches a state in which the network’s fee potential is very close to the maximized fee potential. Similarly almost as many channels as the circuit rank (which is the number of cycles) will be depleted.

Do we know which channels deplete?

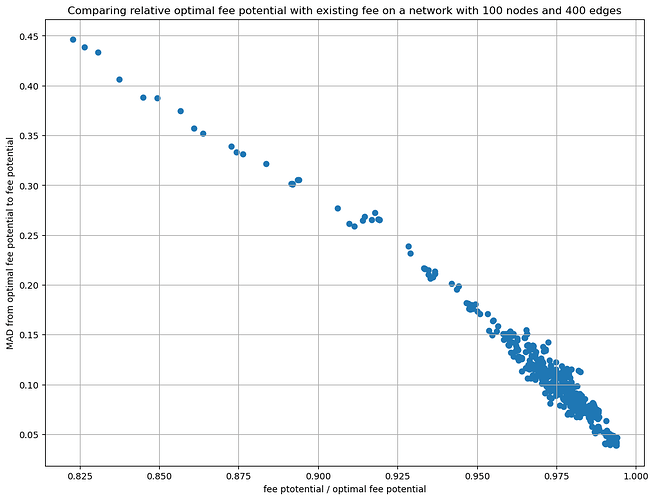

Just because \frac{\phi}{\phi_{opt}}\sim 1 does not mean that the liquidity states are actually similar. Therefor in a final step I computed after each payment also the mean absolute deviation of the current liquidity state and the one that maximizes \phi.

As you can see, only through sending payments the network converges to a liquidity state that can easily be predicted by just solving the integer linear programming problem of maximizing the fee potential with the data from gossip.

With respect to privacy: Yet again I am surprised how much information (in this case about liquidity) we can learn from gossip and the default behavior of software clients.

Limits, Conclusions & Open questions:

I am aware of a few limitations and have some open questions. There is probably more.

Limits:

- Of course the actual distribution of the liquidity depends on the assumed (but unknown) wealth distribution

- In Reality implementations use various cost functions while the simulation only used one.

- While payment dynamics are part of the model the network topology and fees are assumed to be static.

- I used uniformly distributed random payment pairs and uniform payment amounts from 0 to the max flow between the pair. (While unrealistic, I hope it does not change the emergent phenomenon but maybe only the speed with which the phenomenon emerges)

Conclusions

- Most likely much less probing will be necessary to estimate where the liquidity is located

- A spanning tree of non depleted channels remains. This is pretty much a hub and spoke topology.

- The direction of the drain of a particular channel depends on the topology and fees within the entire network (and payment flows). In particular it the ratio of ppms in both directions may be less indicative.

Open Questions:

- Is this evidence enough to conclude that drain on channels and depletion does not come from the existence of sink / and source nodes but would also emerge in a circular economy?

- Can one derive strategies for node operators to adopt fees in their liquidity management strategies?

- Are more channels than a spanning tree useful? I mean obviously they provide redundancy but also depeletion and have on chain cost.

- Similarly, how stable is the location of the spanning tree while the wealth distribution changes.

- Could the bimodel prior that is being used by many implementations be changed to one that estimates liquidity to be on one side or is it useful as the dynamic often changes the side where the liquidity will be located?

- How does the situation change if sending nodes use this knowledge to predict where liquidity is located while solving the optimization problem to send payments?

- Has anyone a good data set to test how accurate the prediction is in comparison to the actual network?