Summary

This post contains a collection of my findings on an attacker being able to eclipse Bitcoin nodes using interception attacks - a stealthier variant of the standard BGP hijack.

Key takeaways: The attack seems to be feasible against many nodes in the network, and I was able to produce a proof-of-concept by attacking my own mainnet node in an isolated environment. To hinder this type of attack, I looked into several mitigations, some of which use networking data that the node can observe independently.

The rest of the post presents the attack in detail, looks into its feasibility, presents findings from a proof-of-concept implementation, discusses networking data that can be used in defenses, and concludes with a description of the proposed mitigations.

Background

BGP and BGP hijacks: BGP is the protocol used by routers in the backbone of the internet to establish routes between a source and a destination. These routers belong to Autonomous Systems (ASes) (e.g: Verizon, AT&T) and exchange announcements about IP prefixes to form paths to them. Because the protocol lacks authentication, an attacker can perform a BGP hijack by making a false announcement that is preferred over the legitimate one by the BGP best path selection algorithm. The attacker then diverts traffic from the legitimate destination to themselves. An attacker can partition Bitcoin this way (see [4]).

Interception (SICO) attacks: This is a stealthier variant of traditional BGP hijacks that also makes it easier to intercept and forward traffic to the legitimate destination. The attacker does this by limiting how their malicious announcements spread by tagging them with metadata known as BGP communities. This allows the attacker to evade BGP route monitors that can detect the attack, and maintain a path to the legitimate destination to forward traffic (see [5], [6] for details).

Details on interception attacks

The attacker announces malicious BGP routes to the IP prefixes to which they want to intercept traffic. In these announcements the attacker claims to be the origin of the IP prefix or a hop in the path to the prefix. Routers that accept the announcement will route their traffic to the legitimate destination through the adversary.

The attacker attaches BGP communities (e.g NoExportSelect, LowerPref) to their announcements to limit their propagation to specific ASes. This makes the attack stealthier and more practical, since announcements are observed by fewer ASes and the adversary attracts less traffic. This also allows the multi-homed adversary AS to maintain a route to the legitimate destination and forward traffic to it, turning the attacker into a man-in-the-middle (MITM).

Eclipse attacks: The goal of the attacker is to control all incoming and outgoing connections to a node. This allows the attacker to waste mining power, do selfish mining, double spend, attack Lightning, etc [1]. This was previously done by polluting AddrMan’s tables with IPs that the attacker controlled [2], or was on the path to [1]. Core has mitigated these eclipsing methods by making changes to AddrMan.

Attack Description

Requirements: The attacker controls a multi-peer AS by either compromising one or setting up their own.

The attacker aims to intercept or control all victim node connections by the end of the attack by taking the following steps:

-

Continuously attempt to occupy incoming connection slots and avoid being evicted. This is done by using addresses in different network groups, relaying blocks and transactions, and having low latency (see [3] for details).

-

Compromise or set up a new AS as close (in number of AS hops) to the victim node AS as possible. This helps the attacker’s announcements to be preferred over legitimate ones by the BGP best path selection algorithm (AS path length criterion).

-

Build a database of known Bitcoin nodes and their IP prefixes. This is done by running a node or using data like that from Bitnodes snapshots, etc.

-

Sort IP prefixes by number of nodes and hijack them in succession at a rate that will not raise alarms. The attacker attaches BGP communities to limit the spread of the malicious advertisements to as few ASes as possible, and maintain a route to forward traffic to the legitimate destination.

-

Observe the intercepted traffic and identify Bitcoin connections by known IPs and ports from Step 3.

-

If no Bitcoin traffic is observed for a hijacked prefix, stop hijacking it

-

If Bitcoin traffic is seen:

-

If the peer’s IP is public, maintain the hijack as it is possibly an outbound connection

-

If it’s an encrypted V2 connection, continue forwarding and intercepting traffic

-

If it’s a V1 connection, impersonate it (or continue forwarding and intercepting)

-

-

If the peer’s IP is private, the connection is inbound. Reset the connection, and then occupy its slot with an attacker-controlled node. Finally, withdraw the route.

-

-

-

Test to see if the victim is eclipsed: submit a transaction to the victim node and drop or delay traffic to the hijacked connections. Then check if the transaction propagates. At this point the attacker only has to maintain up to as many prefix hijacks as the number of connections it intercepts.

Note on asymmetric routing

Because internet routing can be asymmetric, if the attacker wishes to intercept both directions of the communication, they may have to make one additional prefix announcement for the victim’s prefix that targets the routers on the inbound path.

Attack Feasibility

An attacker is successful in launching the attack if they manage to remain unnoticed while hijacking prefixes, and if their malicious BGP announcements are preferred over the legitimate ones. To remain stealthy, an attacker evades route monitors by limiting the spread of their announcements using BGP communities (see [6] for details), hijacking as few prefixes as possible, and doing so at a rate that won’t raise suspicions. The success of the malicious announcement depends on the victim prefixes and the attacker’s position in the network.

To judge the feasibility of the attack, the rest of this section answers the following questions:

-

How many prefixes does the attacker have to hijack at most?

-

Can the attacker hijack these prefixes at a reasonable time frame?

-

How vulnerable are Bitcoin node prefixes to BGP hijacks?

-

What is the probability that the attacker’s announcements will be preferred over the legitimate ones?

1. Number of prefixes

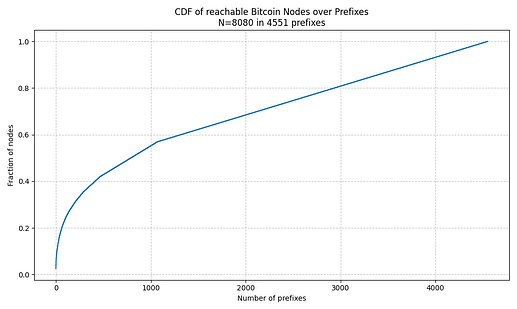

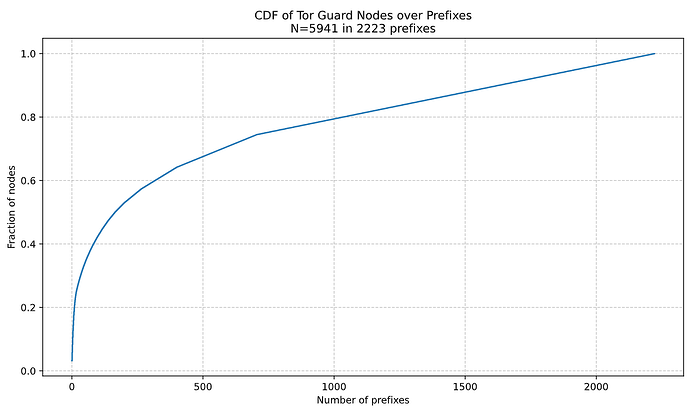

Using a snapshot from Bitnodes we can see that all reachable nodes reside in just 4551 prefixes (the internet has over 1,155,000 allocated prefixes). Furthermore, the attacker can cover more than ~55% of reachable nodes by hijacking just 1000 prefixes.

2. Hijack rate

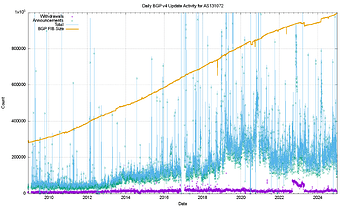

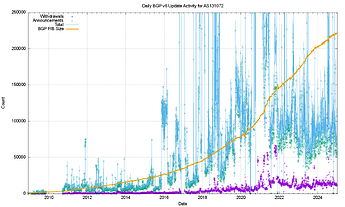

Seeking to remain unnoticed, the attacker limits the rate of their announcements and minimizes the duration for which they remain active. In 2024 BGP routers received on average over 200,000 BGP announcements per day. An attacker seeking to eclipse a node over the course of 10 days will cause just a 0.23% increase in announcement volume if they have to hijack all reachable node prefixes. Furthermore, because the vast majority of malicious announcements do not have to be long lived, they are more likely blend in with benign misconfigurations.

Graphs: Number of BGP route announcements and withdrawals for IPv4 and IPv6 prefixes as observed by a vantage point. Source: Geoff Huston - ISP Column - January 2025

3. Prefix vulnerability

We find that the attacker can always successfully hijack 41.13% of node prefixes either because they have overly permissive ROAs or lack an ROA and use a shorter prefix than the longest one that BGP routers will propagate (see detailed analysis below). For the remaining 59.87% of prefixes, the attacker’s announcement will have to compete with the legitimate one if a router receives both announcements.

Detailed analysis of IP prefix vulnerability

For the attacker to be successful, their route announcement needs to be preferred over the legitimate one by other BGP routers. This depends on a number of factors including the IP prefix having a Route Origin Authorization (ROA) - which only allows the ROA holder to announce the prefix as the origin-, the permissiveness of the ROA, the length of the announced prefix, and the attacker’s topological position in relation to the BGP routers that receive the malicious announcement. We discuss the following 4 possible cases and how the attacker handles them:

Case 1: No ROA, and legitimate prefix length < maximum length - 13.29% of prefixes

The absence of an ROA allows the attacker to announce that they are the origin of the prefix. Because the legitimate prefix announcement is shorter than the maximum length which BGP routers will propagate, the attacker can announce a longer prefix (more-specific), and their announcement will be preferred over the legitimate.

Case 2: No ROA, and legitimate prefix length == maximum length - 4.39% of prefixes

The attacker can still claim to be the origin, and make an announcement with the same prefix length as the legitimate one. The decision between adopting the attacker’s route or the legitimate one will depend on the BGP best path selection algorithm as configured on the router that observes the routes.

Case 3: ROA exists but is overly permissive, and legitimate prefix length < maximum length - 27.84% of prefixes

The existence of an ROA prevents the attacker from announcing themselves as the prefix origin, but allows them to make an announcement where they are the second hop in the path. The attacker can do this regardless of them being connected to the legitimate origin. Because the ROA is overly permissive, the attacker can make more specific prefix announcements, making their announcements preferable to the legitimate ones (see [7] for details).

Case 4: ROA exists but is not overly permissive, or legitimate prefix length == maximum length - 54.48% of prefixes

The attacker cannot claim to be the origin because of the ROA, and instead claims that they are the second hop in the path. Similar to Case 2, the attacker announces the same prefix as the legitimate one and competes with it. Routers that receive both announcements select a path using the BGP best path selection algorithm.

4. Malicious announcement acceptance

For the 59.87% of node prefixes that the attacker’s malicious routes will have to compete with the legitimate ones, the attacker can influence the BGP best path selection algorithm in their favor by placing themselves as close to the victim as possible to influence the AS path length criterion.

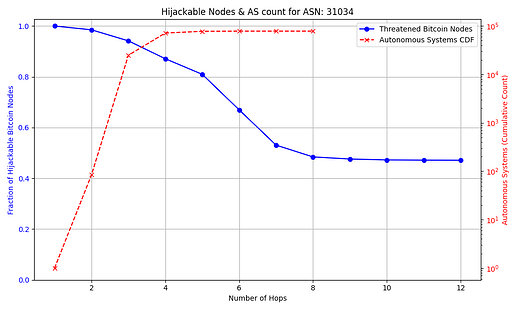

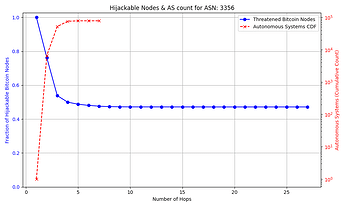

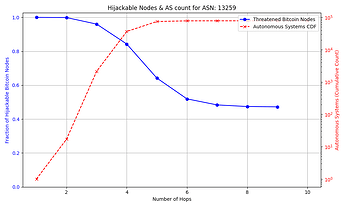

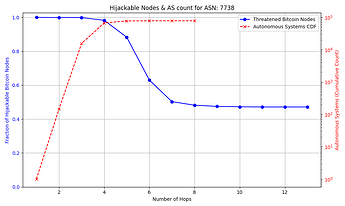

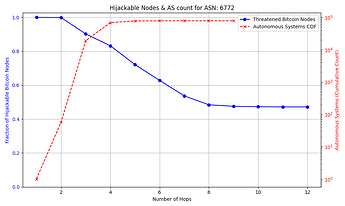

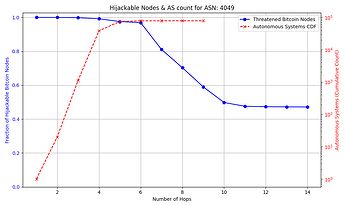

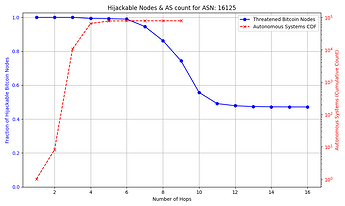

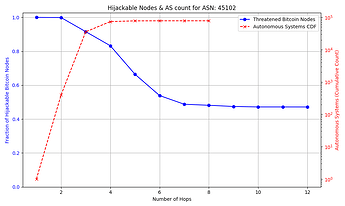

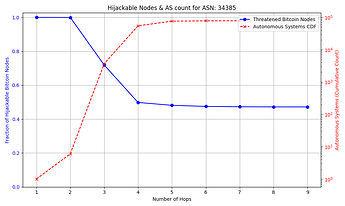

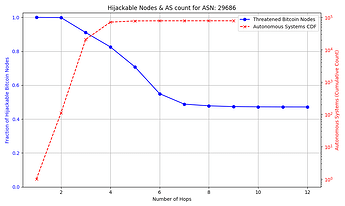

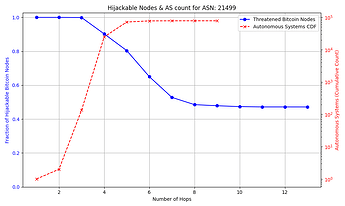

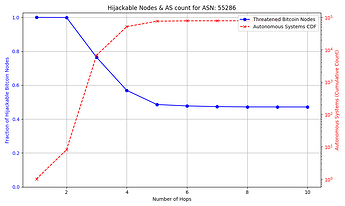

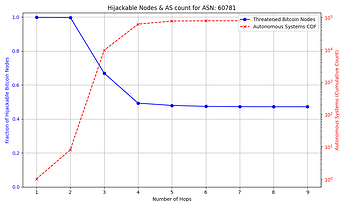

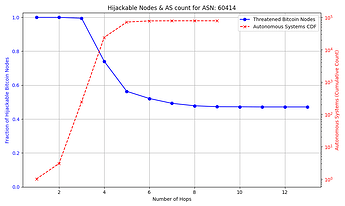

The success rate and feasibility of the attack depends on the victim. The figure below quantifies this for a victim node in AS 31034. The x axis represents the number of hops away (in number of ASes) that the adversary AS is from the victim AS. The y axis shows the number of Bitcoin nodes that the adversary intercepts in blue, and in red the number of ASes that exist up to that number of hops away from the victim AS which the attacker can potentially compromise. For instance, an attacker can compromise one of 10,000+ ASes that are 3 or fewer hops away from the victim, and successfully hijack connections to over 85% of reachable nodes.

Note: some reachable nodes are excluded from the figure (see collapsible section for details).

More details on the malicious announcement acceptance rate study

This analysis studies 13 random “important” nodes (by Bitnodes PIX score) in different regions as the candidate victims. These are nodes with characteristics such as high uptime, low latency, up-to-date block heights etc. that are desirable in nodes that are relied on for commercial activity.

Using the IPs of these nodes, we estimate the paths between them and all other reachable Bitcoin nodes using a path estimation algorithm [8]. By taking into consideration the ROAs, prefix lengths, and AS path length (as determined by the adversary’s hop count away from the victim) we can count the number of nodes for which the adversary’s announcement would be preferred over the legitimate one.

The general trend shown by the figures is that as the distance from the victim node increases, the opportunities for the attacker to compromise or setup their own peering AS also increase, but the number of nodes for which they can successfully make malicious prefix announcements decreases. The plateau that appears on the number of hijackable peers in the graphs is explained by the prefixes that the attacker can always successfully hijack (see Cases 1 & 3 in the collapsible paragraphs in the “Prefix vulnerability” subsection). In cases such as that of the victim node in AS 16125, the attacker can compromise or peer with one of tens of thousands of ASes up to 5 hops away and still be able to make malicious prefix announcements that cover the vast majority of reachable nodes.

Note: due to limitations of the path estimation algorithm, we have excluded the reachable nodes for which we could not calculate a valid route.

Proof of Concept

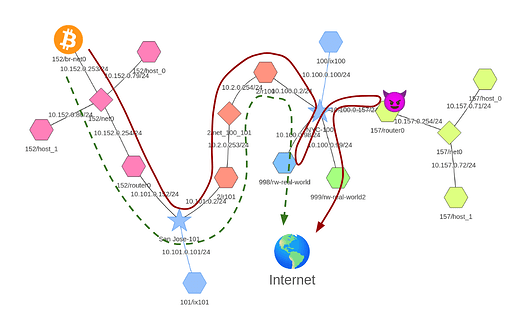

To confirm the feasibility of the attack I emulated a simple AS topology with gateways to the real internet, and eclipsed my own Bitcoin node that was connected to the mainnet. This topology is illustrated in the figure below along with the path that traffic took before and after the attack.

While performing the attack, I noticed that in certain cases, possibly due to reasons related to the emulation environment, some intercepted connections dropped because of a TCP RST packet sent from one of the hops on the path. To overcome this, I ran the attack script 6 more times, at which point I was intercepting all of my node’s connections, including anchor connections. Because anchor connections exchange less traffic, I had to expand the observation time window to ensure that the the attack script had the chance to observe anchor traffic in hijacked prefixes.

Additional emulation details

I emulated the AS topology shown below using SEED. In this topology, AS 152 hosts the victim Bitcoin node which is connected to the emulator via a VPN tunnel. AS 152 peers at Internet Exchange Point (IXP) 101 and peers with AS 2 which provides transit to IXP 100. At IXP 100, AS 998 acts as a provider to AS 2 and is a gateway to the real internet. This means that under normal operation traffic from the victim AS to the real internet flows as follows: 152→ 101→ 2 →100 → 998 → Internet.

The attacker controls AS 157 which peers at IXP 100 and has ASes 999 and 998 as upstream providers. Like AS 998, AS 999 is a gateway to the real internet. AS 999 and AS 998 have a peer relationship with each other. During the attack, AS 157 makes malicious announcements to AS 998 claiming to be the second hop on the path to all reachable nodes. To avoid AS 999 also adopting the malicious routes, which would prevent AS 157 from intercepting and routing the traffic to the legitimate destination via AS 999, the attacker attaches the NoExport BGP community to its announcements.

The attacker proceeds to hijack prefixes as described in the attack algorithm making the traffic from the victim AS destined to the hijacked prefixes flow as follows: AS 152 → 101→ 2 →100 → 998 → 100 → 157 → 100 → 999 → Internet.

Feasibility of using locally-observed path data

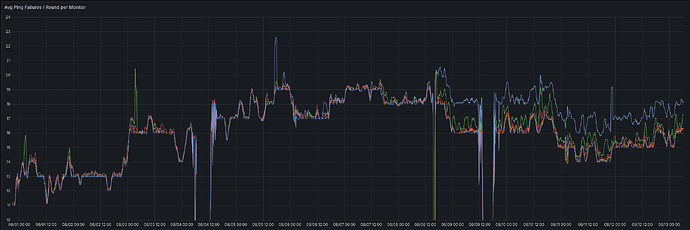

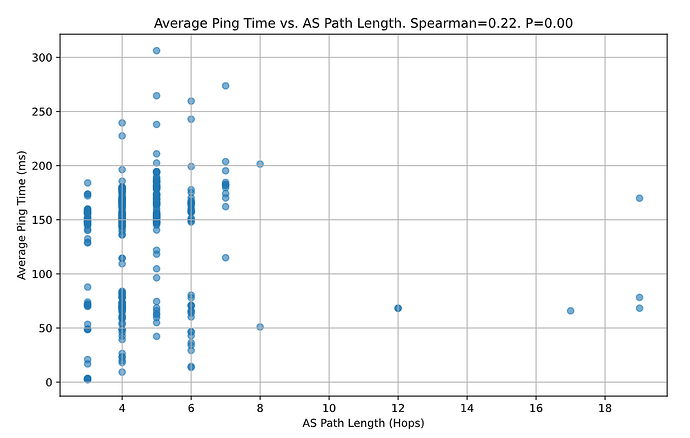

To look for solutions that can detect or mitigate this attack, I wanted to evaluate the possibility of using networking data that can be observed directly by the victim node itself. To do this, I emulated nodes in the network and took periodic network measurements from them to a random sample of reachable Bitcoin node hosts that could act as peers.

Measurement setup details

The measurement setup consists of 6 vantage points deployed in the ASes of Internet Service Providers (ISPs) used by residential users, corporate customers, academic institutions, and cloud providers. These vantage points run CAIDA’s open source scamper tool and receive instructions from a coordination node to make measurements. The coordination node instructs all vantage point nodes to perform pings and traceroutes to a sample of 350 random reachable Bitcoin node hosts every 4 minutes. Results are then gathered by the coordination node to perform post-processing and analysis.

I have been collecting measurements for over a month at this point. I intend to continue measurement collection, further analyze the data, and prepare it for public release.

I share some relevant insights from the collected data:

Insight #1: Host churn is low.

Over the past month, the number of nodes that could not be reached using ICMP pings has increased from 4 to 15-18 in the sample set of 350 reachable nodes.

Insight #2: Traceroutes have a high success rate.

After post-processing, I confirmed that the traceroutes reached the destination AS in 97% of cases. In particular, 43.3% of traceroutes reach the actual host, 47.9% stop because they reach the limit of allowable gaps at the end of the path, 8.17% report the host as unreachable, and 0.06% stop because a routing loop is detected.

Insight #3: Most AS hops on a given path can be reliably inferred.

The worst performing vantage point used for measurements had an average AS path completeness of 75.1%, while the best performing one had 92% AS path completeness. These are conservative estimates where null hops are counted as single ASes. Path inference was done using data collected from BGP monitor nodes, and Internet Routing Registries (IRRs), and using an algorithm informed by AS connectivity and business relationships.

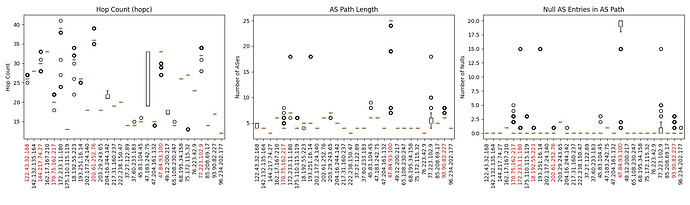

Insight #4: Paths to reachable nodes are generally stable.

This is demonstrated in the figures below that show the number of router hops, number of AS hops, and number of unidentifiable ASes on the paths reported by the traceroute measurements from each vantage point.

In the boxplot, with the exception of a handful of nodes (marked in red on the axes), all nodes had < 5% measurement outliers (marked with Os). In the vast majority of cases, interquantile ranges are equal to 0.

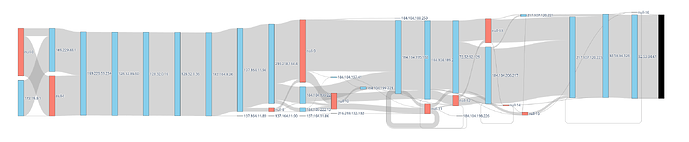

It’s also the case that the path to a given destination is generally stable with regards to the specific routers (and by extension ASes) that appear on the path. The sankey diagram below presents the path that traffic took from one of our vantage points (left side) to a specific destination (right side) over the course of 2000 probes. Loop artifacts in the presentation are because null hops (marked in orange) at a specific hop count are all aggregated into one block.

Insight #5: AS diversity increases during the first few hops before decreasing.

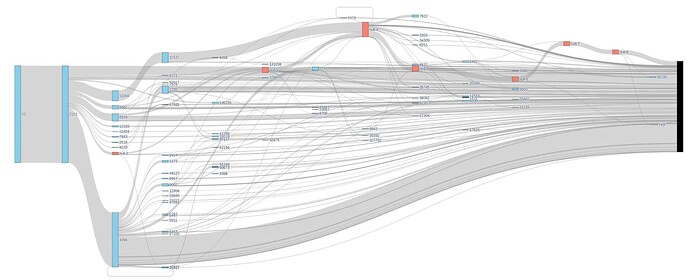

This is illustrated in the sankey diagram below that samples traffic to all 350 nodes and aggregates all destinations and terminal null traceroute hops in the block on the right. All traffic initially flows from AS 25 to 2152 before being it gets split over a set of ASes on the 3rd hop, and then an even larger set on the 4th hop.

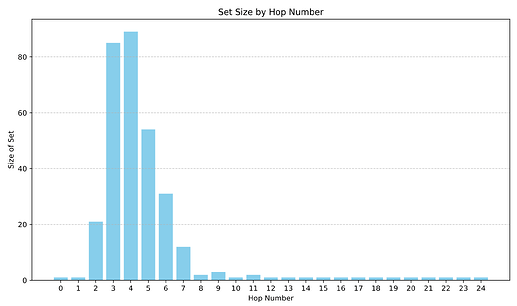

This is also visualized in the following histogram that shows the number of unique ASes that traffic crosses at a given hop count. After the 4th hop, the number of unique available ASes decreases because most traffic has already reached its destination AS. ASes at hop counts > 8 are mostly artifacts of terminating null hops in our traceroutes (e.g “null_15”).

Mitigations

The following are sketches of proposed mitigations that are tagged by them requiring traceroute capabilities by Bitcoin Core [x-T] or not [x-NT].

[1-NT] Peer rotation

Description: We can periodically rotate a subset of our peers, potentially weighted in a way that favors long-term stable connections. This makes it harder for an attacker to settle on a set of hijacked connections and forces them to perpetually be performing hijacks to discover the new connections.

Pros: Only requires making changes to AddrMan.

Cons:

- Nodes might lose good stable connections

- Hard to reason about the effects it will have on the overlay network w.r.t connectivity, latency etc. since nodes that have been online for a long time and have settled on long-lasting stable connections will now be rotating them regularly

[2-NT] Use dynamic port negotiation

Description: Upon first connection, after exchanging version and verack messages, the two peers can optionally negotiate a random pair of ports to continue communications on, making it harder for an attacker who observes traffic beyond the initial interaction to identify connections based on known port numbers. This is inspired by what FTP does in passive mode (PASV).

Pros: Generally raises the bar for passive fingerprinting by on-path eavesdroppers.

Cons:

- NAT / Firewall traversal: Requires one side to be able to dynamically open public facing ports, or building hole-punching coordination into the client.

- Protocol changes: Requires introducing a new type of network interaction

- An adversary with a complete list of Bitcoin node IPs can still spot a connection based on the addresses

[3-NT] Favor peers in protected prefixes

Description: We can make AddrMan prefer connecting to peers in prefixes that are RPKI-protected and have minimal ROAs, or that use the maximum length propagatable by BGP. This makes the attack harder, as the adversary’s malicious routes need to compete with the legitimate ones.

Pros:

- Only requires making local changes to AddrMan

- Preferring maximum-length prefixes does not introduce any new dependencies

Cons:

- Can potentially increase centralization as it will bias connections in favor of peers in protected prefixes

- To check a prefix’s RPKI status, the client needs access to ROA information. This can be obtained using the RTR protocol and processing this information locally, or by querying a remote service (e.g a Routinator instance).

[4-T] Select at least one peer with the shortest path possible

Description: As shown in the Attack Feasibility section, attackers cannot hijack prefixes with minimal ROAs or maximum prefix lengths that are closer to the victim than the attacker. We can thus reserve one of our connection slots for the peer with the shortest AS path from us that is in a protected prefix.

Pros:

- Significantly hinders the attack

- Like [3-NT] preferring maximum-length prefixes does not introduce new dependencies

Cons:

- Requires making Core capable of making periodic traceroutes to candidate peers to judge the lengths of the AS paths to them

- Like [3-NT], requires RPKI information

[5-T] Route-aware peer selection

Description: The idea is similar to that of the ASmap project, or of using network group buckets for peers. However, instead of selecting based on just destination diversity, we do so based on path diversity, exponentially favoring peers whose paths introduce new ASes earlier on.

Pros:

- Only requires local changes and does not require external collaboration

- Can potentially readily leverage the efforts made by the ASMap project to resolve IPs to ASes

Cons:

- Requires making Core capable of making periodic traceroutes to candidate peers to judge the lengths of the AS paths to them

Discussion

I am interested in receiving feedback on the proposed mitigations and discussing alternatives that I might have missed. I would also like to hear people’s thoughts on integrating traceroute functionality into core to enable the aforementioned mitigations.

Acknowledgements

I want to extend my gratitude to the people at Chaincode Labs for their support. Their input has been instrumental in carrying out this research.

References

[1] A Stealthier Partitioning Attack against Bitcoin Peer-to-Peer Network

[2] Eclipse Attacks on Bitcoin’s Peer-to-Peer Network

[3] SyncAttack: Double-spending in Bitcoin Without Mining Power

[4] Hijacking Bitcoin: Routing Attacks on Cryptocurrencies

[5] SICO: Surgical Interception Attacks by Manipulating BGP Communities

[6] Global BGP Attacks that Evade Route Monitoring