We propose a method of emulation of OP_RAND opcode on Bitcoin through a trustless interactive game between transaction counterparties. The game result is probabilistic and doesn’t allow any party to cheat and increase their chance to win on any protocol step. The protocol can be organized in a way unrecognizable to any external party and doesn’t require some specific scripts or Bitcoin protocol updates. We will show how the protocol works on the simple Thimbles Game and provide some initial thoughts about approaches and applications that can use the mentioned approach.

Intro

Bitcoin script doesn’t directly allow putting randomness and constructing the spending flow based on that. So, realizing the flow “Alice and Bob put for 5 BTC each, and Bob takes everything if the coin comes up tails” wasn’t possible upon the following assumptions:

- The transaction can’t derive or take randomness from somewhere at the moment of confirmation

- Bitcoin Script can’t inspect the block, past or future transactions

- Each party can receive the same stack’s state after each opcode processing

- We can’t control the ECDSA or Schnorr signature determinism

- Bitcoin doesn’t support OP_RAND opcode =)

All the limitations mentioned led to the situation where we couldn’t find trustless solutions that allow scrambling randomness and use it for a trustless protocol operating with bitcoins. We propose a way to organize it via a 2-party interactive protocol and show how these properties can be applied in the example of a thimbles game that takes bids in BTC.

Preliminaries

\mathbb{G} a cyclic group of prime order p written additively, G \in \mathbb{G} is the group generator. a \in \mathbb{F}_p is a scalar value and A \in \mathbb{G} is a group element. \mathsf{hash}_p(m) \rightarrow h\in \mathbb{F}_p is the cryptographic hash function that takes as an input an arbitrary message m and returns the field element h. \mathsf{hash}_{160}(P) \rightarrow \mathsf{addr}\in \mathcal{A} is the function of hashing the public key with sha-256 and ripemd160 functions and receiving a valid bitcoin address as an output.

We define the relation for the proof \pi as \mathcal{R} = \{(w;x) \in \mathcal{W} \times \mathcal{X}: \phi_1(w,x), \phi_2(w,x) , \dots, \phi_m(w,x)\}, where w is a witness data, x is a public data and \phi_1(w,x), \phi_2(w,x) , \dots, \phi_m(w,x) the set of relations must be proven simultaneously.

We define a bitcoin transaction as \mathsf{TX}\{(\mathsf{id, i, proof})^{(n)};(\mathsf{a BTC, cond})^{(m)}\} with n inputs and m outputs, where \mathsf{id} is the hash of the previous transaction, i - output’s index, \mathsf{proof} - the list of data which is needed to transaction spending, a - the number of coins in the output, \mathsf{cond} - scriptPubKey conditions. For example, the P2PKH method requires \mathsf{proof} \leftarrow \langle \mathsf{PK}, \sigma\rangle and \mathsf{cond}\leftarrow \langle OP_DUP, OP_HASH160, \mathsf{addr}, OP_EQUALVERIFY, OP_CHECKSIG \rangle. We are going to simplify the condition notation above to \mathsf{addr} when referring to the P2PKH approach.

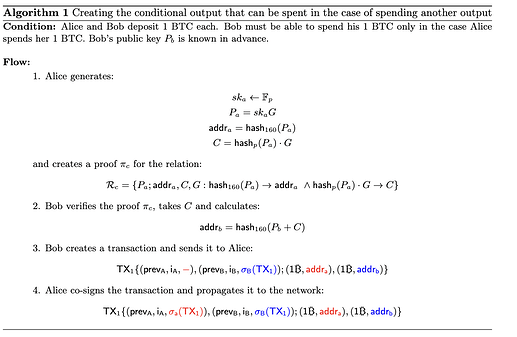

EC Point covenant

First of all, let’s see how we can implement the transaction with two counterparties and the following conditions: “It’s possible to spend the second transaction output only in the case the first is spent”. Traditionally, it could be organized using a hash lock contract, but 1 – it’s recognizable; 2 – it won’t help us to implement the final game.

If Alice wants to spend her output, she needs to create a transaction and reveal a public key P_a and the signature value.

After the transaction is published, Bob can extract P_a and recover the \mathsf{hash}_p(P_a) value. Then the secret key for the second output is calculated as sk = \mathsf{hash}_p(P_a) + sk_b (only Bob controls sk_b), and Bob can construct the signature related to P_b+C public key and corresponding address.

So, we have built the first part needed for emulating the randomness and our thimbles game. We need to note that in the previous example, if Alice doesn’t spend her output and doesn’t publish P_a anywhere, Bob can’t recover the key and spend his output as well. If we need to provide an ability to spend these outputs after some time (if the game hasn’t started), we can do it similarly to the payment channel construction — lock coins to the multisignature and create a tx that can spend them after a defined period.

OP_RAND emulation protocol

We propose to emulate the OP_RAND opcode with an interactive protocol between parties involved in the transaction. Introducing the Challenger \mathcal{C} and Accepter \mathcal{A} roles we can define the OP_RAND emulation protocol as follows:

- \mathcal{C} and \mathcal{A} have their cryptographic keypairs \langle sk_{\mathcal{C}}, P_{\mathcal{C}}\rangle and \langle sk_{\mathcal{A}}, P_{\mathcal{A}}\rangle. Only P_{\mathcal{C}} value is public

- \mathcal{C} generates the set of random values a_1, a_2,\dots, a_n and creates a first rank commitments for them as A_i = a_iG, i\in[1, n]

- \mathcal{C} selects one commitment A_x, assembles it with own public key as R_{\mathcal{C}} = P_{\mathcal{C}}+A_x and publishes only the hash value of the result \mathsf{hash}(R_{\mathcal{C}})

- \mathcal{C} creates second rank commitments as h_i = \mathsf{hash}(A_i), i \in[1,n] and third rank commitments as H_i = h_iG, i \in[1,n]

- \mathcal{C} creates a proof \pi_a that all third rank commitments were derived correctly, and one of the first rank commitments is used for assembling with P_{\mathcal{C}}

- \mathcal{C} proposes the set of third rank commitments to the \mathcal{A} and provides \pi_a

- \mathcal{A} verifies the proof \pi_a and selects one of the third-rank commitments H_y to assemble it with P_{\mathcal{A}}. The result R_{\mathcal{A}}=P_{\mathcal{A}}+H_y is hashed \mathsf{hash}(R_{\mathcal{A}}) and published

- \mathcal{A} creates a proof \pi_r that one of the third rank commitments was used for assembling with P_{\mathcal{A}} and sends it to \mathcal{C}. Additionally the proof covers the knowledge of the discrete log of P_{\mathcal{A}}

- \mathcal{C} verifies the proof \pi_r and if it’s valid publishes the R_{\mathcal{C}}

- \mathcal{A} calculates A_x = R_{\mathcal{C}}-P_{\mathcal{C}}

- If \mathsf{hash}(A_x)\cdot G = H_y, \mathcal{A} won. Otherwise lost

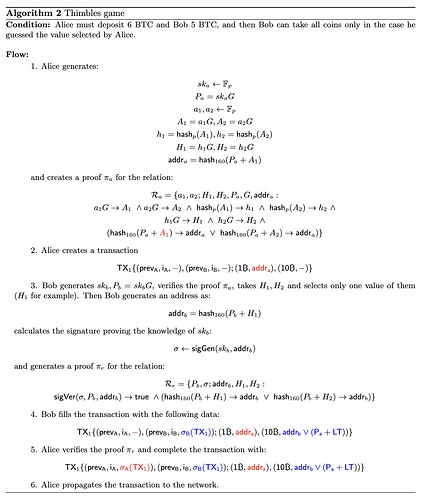

An example of Thimbles Game

Finally, we can show how the interactive protocol we introduced allows the organization of a trustless thimbles game between two counterparties. So, having Alice and Bob, the game could be described as follows:

- Alice and Bob lock their coins.

- Alice generates two values and selects one of them (don’t reveal the selected value to Bob). In other words, Alice chooses a thimble with a ball under it.

- Bob selects the thimble: takes value from proposed by Alice (and also doesn’t reveal it).

- Alice reveals the value she selected initially.

- If Bob selected the same value — he can take all deposited coins. If not, Alice can spend coins after locktime.

So Bob doesn’t know which value was selected by Alice, Alice doesn’t know what Bob selected. And we can go to the final stage when Alice takes her coins. For that Alice spends the first output, so publishes P_a + A_1 value. Bob knows P_a so he can easily receive A_1 value and corresponding h_1 = \mathsf{hash}_p(A_1).

If the secret key h_1 + sk_b satisfies the address \mathsf{addr}_b, Bob can take 10 BTC , locked on the second output. If not — Alice can spend them after the timelock.