Writing with an update on the work that Clara and I have been doing to investigate the effectiveness of our hybrid mitigation for channel jamming attacks against lightning. This post assumes familiarity with the proposal, so please check out the high level write up here if you need to catch up.

tl;dr:

- The mitigation performs as expected against slow and fast jamming attacks, appropriately compensating nodes that are attacked.

- It is resilient against most reputation-spoiling attacks, but needs to be updated to protect against a downstream attacker that opportunistically holds HTLCs to ruin reputation along the route.

PSA: Sections with in-depth details are in collapsable summaries.

🫶 Please click on them for more detail 🫶Introduction

Our reputation algorithm is designed to ensure that the cost of acquiring reputation is comparable to the damage that can be done by abusing that reputation. If there is no revenue loss under attack, we can ensure that nodes are not economically damaged by attacks [0].

Note that we do not guarantee that jamming attacks cannot occur, only that nodes targeted will be compensated by at least the amount that they would have earned with regular operation.

While we can’t possibly enumerate every possible attack, one of the best ways to understand how this mitigation performs is to try to break it and see what happens. So we got a group of lightning developers together earlier in the year for an “attackathon” where they experimented with various approaches to breaking our mitigation.

This post reports on the performance of our mitigation under the various attacks, and outlines improvements made to the proposal based on insights gained from the attackathon.

Attacks

As is the case with any jamming mitigation, there is a risk that the mitigation itself is abused to restrict the resources of the network. In our case, this would be achieved by targeting a node’s reputation to restrict its ability to operate. We therefore need to think about two different approaches to jamming attacks in the context of this solution:

Resource jamming: aims to consume all channel resources, as we think of jamming attacks today. Successfully executed when:

- All general resources have been exhausted by the attacker.

- All protected resources have been exhausted by the attacker

Reputation jamming: aims to render protected resources unusable by sabotaging the reputation of a node’s peers, effectively jamming the channel because the mitigation does not assign these resources to honest peers. (h/t: Thomas for first flagging this one!) Successfully executed when:

- All general resources have been exhausted by the attacker on the targeted channel.

- All of the target node’s peers have low reputation with it.

Resource attacks

Two teams at the attackathon wrote resource jamming attacks, where they aimed to build up reputation with a target node then leverage it to occupy all of its protected resources. We’ve since built out these attacks and run them against a 50 node test warnet to get an understanding of their impact.

Full details about our test network are available here.

We used real lightning nodes in our resource jamming experiment so that we could capture all the nuance of pathfinding, dust limits and force closures that you need to be conscious of when thinking about channel jamming. We also wanted to create an approachable network that anyone could try to break, rather than a specialist simulator that would likely lack the APIs required to explore different attack approaches.To create a large network, we used warnet to create a test network of LND nodes running our reputation mitigation [1]. We reduced the mainnet graph to 50 nodes using a random sample of the neighborhood around the Acinq node, which was our target node for attacks (sorry Acinq!). Using warcli’s import_json command, we could then spin up a lightning network with the channels and policies of the reduced mainnet graph. None of this would have happened without Zip and the warnet team, I am many beers indebted!

Running with realistic payment history and traffic was important to testing our mitigation in a dynamic environment. We used sim-ln, which can run against real lightning nodes or as a sped up payment simulator to create activity for a given graph, in several places:

- Reputation bootstrap: running in simulation mode for the chosen graph, we generated payment histories for honest nodes which were imported to our reputation system to provide historical data without having to execute months of payments on the actual nodes.

- Honest payments: running connected to every honest node in the network, we generated honest payment activity in the network during the attack.

- Projected revenue: running in simulation mode with the same fixed seed as the honest payments, we generated a projection of the payments that nodes in the network would have processed in the absence of a jamming attack. We generated these projections 50 times for the network, and used the mean to represent the network in peace times.

This payment traffic is, of course, an imperfect representation of mainnet traffic. It does however provide a baseline for comparison across attacks and peacetime for the simulations.

Some of the time-based parameters in our proposal were reduced to shorten our runtime:

- Revenue window = 1 hour

- Reputation window = 24 hours

- HTLC opportunity cost = 12 blocks

- Block time = 5 minutes

Slow Slot Jamming

We ran a slow slot jamming attack against a single channel on our targeted node, aiming to consume > 480 slots on the target channel for a period of 10 minutes.

An in depth description of the attack strategy is available here.

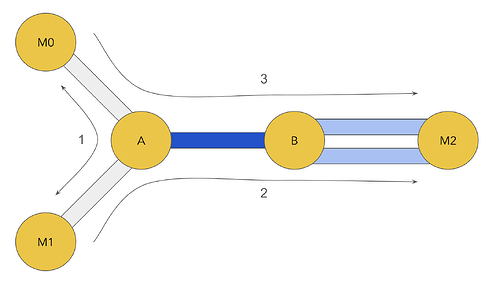

The approach taken to orchestrate a slow jamming attack against the target channel A-B by malicious nodes M0/1/2 works as follows:- M0 “pre-pays” good reputation with A on M0-A by sending fast-resolving, successful payments over M0-A-M1.

- These payments do not need to be endorsed, because fast-resolving successful unendorsed payments will bootstrap their reputation.

- Note that we don’t want to build a reputation on a path that utilizes A-B, because this would inflate the value of AB for M0 to later attack.

- M0 will occasionally send an endorsed payment probe over M0-A-B-M2 to determine whether they’ve built sufficient reputation to use A-B’s protected resources.

- Once M0 has built up sufficient reputation, M1 sends a set unendorsed payments over M1-A-B-M2 to occupy all of the general resources on A-B and holds them for the duration of the attack.

- Finally, M0 will send a series of endorsed payments over M0-A-B-M2 to occupy all of the protected resources on A-B and hold them for the duration of the attack.

- This can be fine-tuned to distinguish between reputation-based and liquidity based failures by iteratively probing and “pre-paying” for more reputation (as described in (1) to ensure that M0 does not overpay for access to the protected slots.

- It’s likely that A doesn’t have sufficient reputation with B to occupy all of its protected resources on its channels with M2, so two channels are opened so that all jamming payments can be accommodated in the general buckets of the channels between B and M2.

In our experiment, the mitigation strategy worked as expected - the targeted node did not lose revenue when targeted, and the majority of attacker costs were for reputation building.

Attacker paid: 1,370,485 msat in off-chain fees:

- Success case (94% of total): 1,286,744 msat

- Unconditional (6% of total): 83,740 msat

Target earned: 1,875,080 msat in off-chain fees:

- Success case (97% of total): 1,815,280 msat

- Unconditional (3% of total): 59,799 msat

The target was paid 1,446,343 msat in off-chain fees by the attacker, so their revenue breakdown is:

- 93% of revenue paid by attacker traffic

- 7% of revenue was paid by honest traffic

To compare revenue under attack to the target node’s expected revenue in times of peace, we ran our payment simulator 50 times to get an average expected revenue of 15,030 msat over 10 minutes and 1,205,876 msat over a 2 week period.

Since the HTLCs for the slow jamming attack can be held for up to two weeks, we compare our attacker costs to projected revenue over a two week period. There is a 19.94% increase in revenue for the targeted node under attack. This is not surprising, because our per–htlc “opportunity cost” charges quite a steep fee for each slot in our protected bucket of resources [2].

Raw data for the experiments is available here.

| ID | Success case fees paid by attacker | Unconditional fees paid by attacker | Success case fees earned by target (all senders) | Unconditional fees earned by sender (all senders) | Fees paid from attacker to target | Time Slot Jammed (>440) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,286,350.00 | 82,463.50 | 1,291,127.00 | 53,511.27 | 1,339,813.50 | 10.09 |

| 1 | 1,296,305.00 | 88,347.05 | 1,308,725.00 | 57,131.25 | 1,353,242.05 | 10.18 |

| 2 | 1,292,105.00 | 88,305.05 | 2,144,659.00 | 65,470.97 | 1,349,000.05 | 10.38 |

| 3 | 1,296,305.00 | 88,347.05 | 1,308,658.00 | 57,080.58 | 1,353,242.05 | 10.45 |

| 4 | 1,274,705.00 | 88,107.05 | 1,290,544.00 | 56,895.44 | 1,331,412.05 | 10.38 |

| 5 | 1,292,105.00 | 88,305.05 | 1,301,111.00 | 57,015.11 | 1,349,000.05 | 10.12 |

| 6 | 1,293,505.00 | 76,751.05 | 1,307,637.00 | 50,363.27 | 1,343,666.05 | 10.03 |

| 7 | 1,272,837.00 | 76,520.37 | 1,283,632.00 | 50,108.96 | 1,322,777.37 | 10.13 |

| 8 | 1,272,837.00 | 76,520.37 | 1,283,365.00 | 50,055.65 | 1,322,777.37 | 10.06 |

| 9 | 1,290,394.00 | 82,503.94 | 1,296,973.00 | 53,619.73 | 1,343,897.94 | 11.02 |

| MEAN | 1,286,744.80 | 83,740.73 | 1,391,050.89 | 55,292.50 | 1,340,547.84 | 10.20 |

| STDDEV | 10,102.26 | 5,678.04 | 282,789.65 | 4,968.40 | 12,198.72 | 0.1582123597 |

| MEAN/STDDEV | 127.37 | 14.75 | 4.92 | 11.13 | 109.89 | 64.47496481 |

Fast Slot Jamming

This attack is a variation on the slow jamming attack described above, where the targeted node’s protected resources are occupied by a continuous stream of fast-failing payments. This was particularly interesting to us, because it manages to exhaust protected resources without the attacker losing their reputation. In this attack, the targeted node is protected only by unconditional fees, and the eventual decay of the reputation that the attacker built up to gain access to the protected bucket in the first place.

When unconditional fees will be a major cost to the attacker, it’s worth examining whether slot or liquidity jamming will be more economical to fully occupy the channel’s resources. The costs that we need to consider are:

- Reputation cost: the amount paid to gain access to protected resources, generally expected to be higher for liquidity jamming because this cost depends on the fee for the HTLC.

- Unconditional fee cost: the unconditional fee paid to continuously occupy protected resources with many slot jamming payments or fewer larger liquidity jams; dependent on the fee policy of the targeted channel.

We ran this comparison against a snapshot of the mainnet graph and found that it’s more economical to fast slot jam 59% of the channel policies on the network.

As was the case with our slow jamming attack, the mitigation performs as expected and the targeted node is compensated for the revenue that it would lose in the window that it is jammed. But unlike a slow jamming attack, the attacker does not lose their “prepaid” reputation so they will be able to continue the fast jamming attack until their reputation decays.

To keep the channel jammed, the attacker will need to continuously dispatch fast-failing payments to occupy the protected resource on a channel. For an attack time t (expressed in seconds) the total unconditional fees that they will have to pay for a fast-slot attack is: t / 90 * 242 * base_fee * 0.01.

This produces 32,524,833 msat in unconditional fees for our targeted channel to continue the attack for 2 weeks (given a base fee of 1000 msat). This represents a 25% increase in revenue when targeted by a fast slot jamming attack. We also sanity checked this result against a liquidity jamming attack, which requires fewer HTLCs with higher reputation “costs”, and saw similar revenue numbers.

Raw data for the experiments is available here.

| ID | Success case fees paid by attacker | Unconditional fees paid by attacker | Success case fees earned by target (all senders) | Unconditional fees earned by sender (all senders) | Fees paid from attacker to target | Time Under Attack (>440) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,288,839.00 | 157,248.39 | 1,300,920.00 | 97,249.20 | 1,385,937.39 | 7.96 |

| 1 | 1,263,505.00 | 156,923.05 | 1,282,525.00 | 97,043.49 | 1,360,308.05 | 7.03 |

| 2 | 1,288,839.00 | 152,016.39 | 1,295,841.00 | 94,136.41 | 1,382,885.39 | 6.00 |

| 4 | 1,221,960.00 | 141,243.60 | 1,245,060.00 | 87,764.60 | 1,309,443.60 | 8.74 |

| 5 | 1,293,505.00 | 172,247.05 | 1,302,040.00 | 106,002.41 | 1,399,372.05 | 7.86 |

| 7 | 1,293,505.00 | 124,055.05 | 1,304,477.00 | 77,934.87 | 1,371,260.05 | 9.97 |

| 9 | 1,293,505.00 | 125,351.05 | 1,297,040.00 | 78,586.47 | 1,372,016.05 | 10.44 |

| 10 | 1,274,392.00 | 136,631.92 | 1,278,920.00 | 85,067.23 | 1,359,403.92 | 10.42 |

| 11 | 1,204,851.00 | 183,504.51 | 1,215,927.00 | 112,195.27 | 1,316,915.51 | 6.01 |

| 12 | 1,292,060.00 | 182,582.60 | 1,300,087.00 | 112,032.87 | 1,403,962.60 | 9.35 |

| MEAN | 1,271,496.10 | 153,180.36 | 1,282,283.70 | 94,801.28 | 1,366,150.46 | 8.38 |

| STDDEV | 32,395.54 | 21,650.22 | 29,342.54 | 12,596.60 | 31,596.28 | 1.68 |

| MEAN/STDDEV | 39.25 | 7.08 | 43.70 | 7.53 | 43.24 | 4.97 |

h/t: Jules/Sachin/Kevin for this one!

Reputation attacks

We also saw a variety of approaches to trying to abuse the reputation system. Two themes emerged across the various attacks:

- Optimization: attacks that attempt to decrease the cost of acquiring good reputation with a target node.

- Manipulation: strategies for using the reputation system itself to cut off honest nodes from access to protected resources.

Optimization - Laddering Attack

A laddering attack exploits a chain of nodes with increasing reputation to gain endorsement with a higher-value node downstream. Since reputation is related to fee revenue, an attacker can identify a chain of gradually increasing channel sizes (assuming that size is a proxy for activity) and build reputation with the cheapest rung of the ladder.

A detailed walkthrough of this concept is available here.

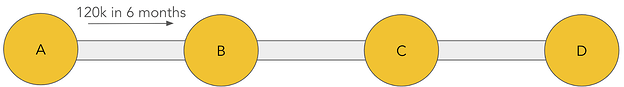

Starting with an honest network of A, B, C, D, we’ll assume that we have the following “laddered” (increasing) traffic pattern:

- Payments sent over A -> B represent 100% of A’s outgoing traffic.

- Payments sent over A -> B represent 10% of B’s forwards on BC

- Payments sent over B -> C represent 25% of C’s forwards on CD

- Payments sent over C -> D represent 50% of D’s forwards onwards.

To keep things simple for the sake of an example, we’ll walk through revenue flows between the nodes without thinking about fee calculations - so when you see 120k of reputation/revenue, think “120k of traffic’s fees of reputation/revenue”. We’ll also assume that traffic is constant over time, so that we can easily move between 2 week and 6 month horizons.

Over a period of 6 months, A forwards 120k of payments to B that will use the BC outgoing link:

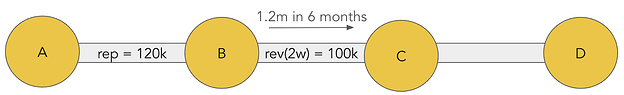

This means that A will have accrued 120k of reputation with B over a period of 6 months. We can then calculate the reputation threshold for B’s outgoing link as follows:

- A is 10% of B’s traffic, so the total traffic over 6 months is 120k * 10 = 1.2m

- The revenue threshold for the outgoing link BC is 1.2m/12 = 100k because we consider our outgoing revenue over a 2 week period.

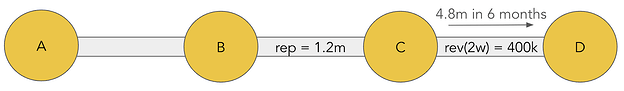

This means that B will have accrued 1.2m of reputation with C over a period of 6 months. Likewise we’ll calculate the reputation threshold of C’s outgoing link as follows:

- B is 25% of C’s traffic, so the total revenue over 6 months is 1.2m * 4 = 4.8m

- The revenue threshold for the outgoing link CD is 4.8m/12 = 400k because we consider our outgoing revenue over a 2 week period.

An attacker looking to perform a laddering attack would aim to build good reputation with A, so that they can get HTLCs endorsed on the more valuable downstream C -> D link. An attacker would need to pay 10k to obtain good reputation with A (120k/ 12 = 10k), and additionally pay for the opportunity cost of any HTLC that they’d like A to endorse.

To get an idea of the damage that an attacker can do with this laddering attack, we look at the difference in A’s current reputation and B’s revenue threshold: 100k - 120k = 20k. This represents the total “budget” that is available for in-flight HTLCs before A’s reputation drops below B’s revenue threshold.

Using our HTLC opportunity cost function, we can calculate the largest HTLC that A can get endorsed based on this budget: budget = htlc_amt * blocks_till_expiry * 10 * 60 / 90. Assuming that a HTLC forwarded on A will expire after 160 blocks, the largest HTLC that an attacker can get endorsed by A (and thus downstream on CD) in 17 msat, which is insufficient to jam the protected resources along the route.

This example deals with toy numbers, but it should give you a general idea of how this type of attack would work. We’ve created a spreadsheet here which allows you to plug in different values to get a grasp on how these numbers work out (make a copy to change the values!).

We wrote a basic fuzzing test for this attack with the following conditions:

- Create a ladder of nodes with 1-8 hops between the attacker and the laddering target

- Traffic must increase with each hop in the ladder

- The target node must have sufficient reputation to get a $1 HTLC endorsed with its peer [3].

- The attack is successful both of the following hold:

- Acquiring reputation via the ladder is less expensive than doing so directly with the target node.

- Using the ladder to slow jam the target node results in it losing reputation with its downstream peer.

We ran the fuzzer for ~24H (~ 23 billion execs) and did not produce any effective ladder attacks. While this of course doesn’t mean that there are no cases where this attack could work, our manual efforts and the fuzzer couldn’t find one!

Manipulation - Surge Attack

In this attack, the attacker inflates the value of the outgoing channel instead of trying to build a direct reputation with the node. By sending many successful payments over the channel, the attacker can drive up the threshold for good reputation, and potentially price out the node’s peers so that they lose access to its protected resources. A key insight here is that the attacker does not need to pay up to the reputation threshold of the channel, just the difference between its peers’ incoming reputation and the outgoing channel’s revenue.

We also fuzzed this attack for ~24H (~22 billion execs) with the following conditions, and did not find any attacks where the targeted node loses revenue to the attack:

- Create a set of 2-255 peers for the targeted node.

- Generate 6 month revenue values for each peer, restricted to < 1 BTC.

- Choose a cutoff point for the attack:

- Sort peers by ascending fee revenue order.

- Choose an index that represents the highest value peer that will be cut off.

- The cutoff peer must have sufficient reputation to get a $1 HTLC endorsed.

- The attack is successful if the sum of the total paid by the attacker to inflate the link and its remaining revenue (not targeted in the surge attack) is less than its revenue when not under attack.

Manipulation - Sink Attack

A sink attack aims to decrease the reputation of a targeted node’s peers by creating shorter/cheaper paths in the network, and sabotaging payments forwarded through its channels to decrease the reputation of all the nodes preceding it in the route.

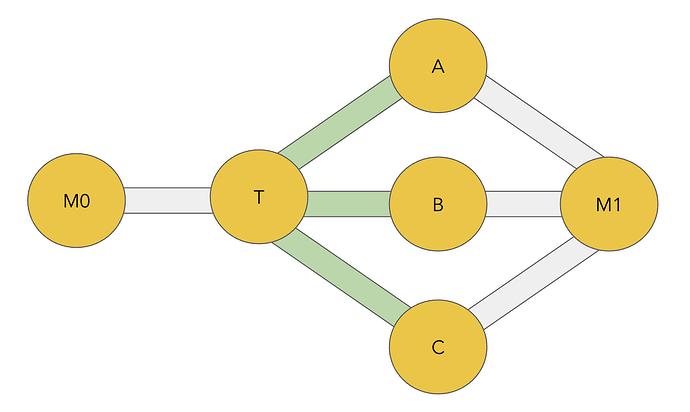

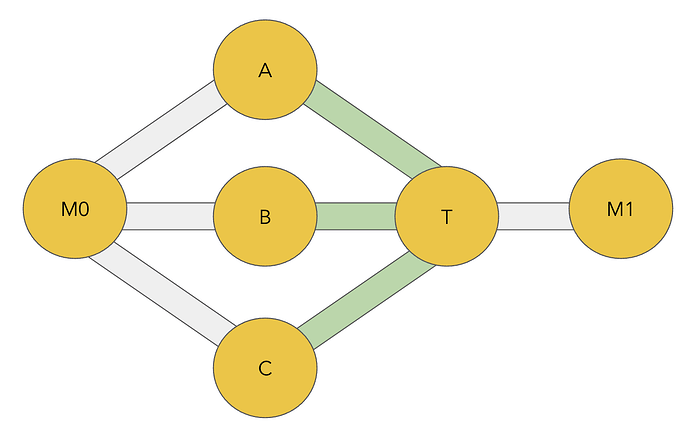

We ran this attack against our test network of 50 nodes with the following strategy (massive thanks to Moorehouse for the code!):

- Attacking node opens zero-fee channels with the 10 largest nodes that are not directly connected to the target node, and a single channel with the target.

- Endorsed HTLCs are held by the attacking node for 5 hours, then released to reach their eventual destination.

- General jam the target node’s channels once its peers have lost their reputation.

This attack successfully reduced the target node’s revenue to 15% of its peacetime revenue, with the only cost to the attacker being 11x channel opens and some minor unconditional fees for the payments used to jam the target’s general slots. This is possible because our mitigation only accounts for the risk of a jamming attack by our incoming link, but does not account for the damage that our outgoing link can do by holding HTLCs.

It’s tempting to think about attributable errors and latency aware routing to fight against an attack that depends on attracting traffic along a route to be successful, because nodes would route around the attacker after one delayed payment [4]. However this attack will still be successful if the attacker can lure in sufficient distinct senders to ruin the target node’s reputation. We could also consider pathfinding that avoids newer links, but we think that’s an unacceptable centralization tradeoff (and a patient attacker can just prepare in advance).

So we’re proceeding with the assumption that an attacker will be able to draw in a reasonable amount of traffic with a well placed, cheap set of channels - please let us know if you think we’re wrong about this [5]! We’re also primarily concerned with slow jamming in this case, because it’s unlikely that an attacker will be able to draw in the volume of payments required to fast-jam a channel entirely.

Bidirectional Reputation

To update our solution to account for the risk that our outgoing link will jam us, we consider reputation bidirectionally [7]. This means that when a payment is forwarded over A - B - C, the forwarding node will consider both A’s reputation as an incoming node and C’s reputation as an outgoing node when it makes forwarding decisions.

A’s incoming reputation is calculated as outlined in our original proposal, and we additionally consider the following values for C’s reputation as an outgoing node:

outgoing_channel_reputation: the total fees that C has earned as an outgoing link over 6 months (the reputation_window in our proposal).in_flight_risk: the outstanding risk of all outgoing HTLCs currently held by C.incoming_channel_revenue: the bidirectional revenue that A has earned us over 2 weeks (the revenue_window in our proposal).

Similar to the incoming direction, C will be considered to have good reputation in the outgoing direction if: outgoing_channel_reputation - in_flight_risk >= incoming_channel_revenue

Here we compare the value that C has offered us as an outgoing link to the value that we may lose if C uses this HTLC in an attempt to jam A. By enforcing this inequality in both directions, we ensure that we have been compensated for any damage an attacker in either direction may inflict.

Forwarding Decisions

In the original proposal, we consider risk to both our resources and reputation when we receive a HTLC from an incoming peer and make our forwarding decision. When a HTLC is not endorsed by a high reputation peer:

- Resources: we limit resource usage to the general bucket of the outgoing channel, so that it cannot be saturated.

- Reputation: we drop the endorsement signal to protect our reputation with the downstream peer.

Likewise, we should consider the risk to our resources and reputation when we forward HTLCs on to an outgoing peer:

- Resources: we have a HTLC locked in on the incoming link, possibly using protected resources, which the outgoing peer may use for slow-jamming.

- Reputation: if the HTLC was endorsed by our incoming peer, the outgoing peer may use it to trash our peer’s reputation by delaying resolution.

When considering the risk that an outgoing peer poses to us, we don’t have the option to drop the endorsement signal and minimize resource utilization to protect ourselves against attack; we’ve already committed to an incoming HTLCs. To fully protect against malicious outgoing peers, forwarding nodes will need to drop endorsed HTLCs if the outgoing peer has low reputation.

Rather than endorse all HTLCs, we suggest that HTLCs are unendorsed by default and only endorsed if the sending node experiences payment failures [7]. We tested endorse-on-failure payments against a test network of 50 nodes and saw no significant decrease in forwarding node revenue, and observed that less than 0.5% of payments were dropped due to this new mechanism.

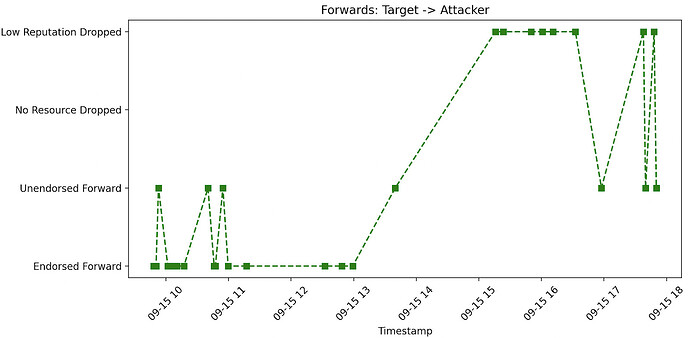

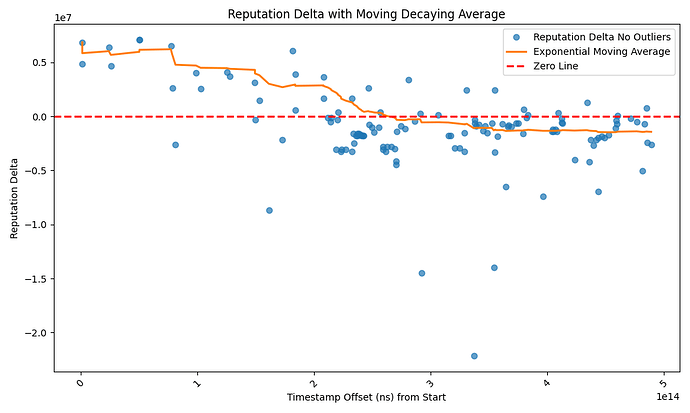

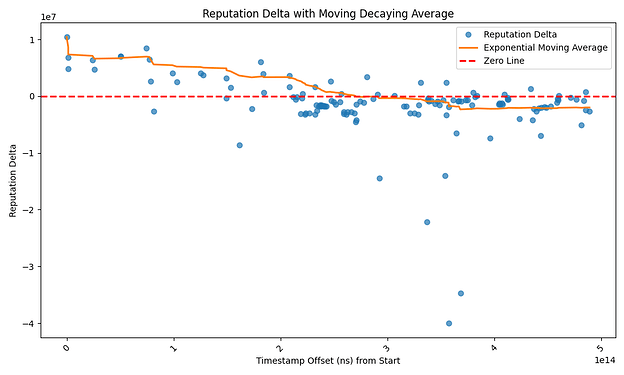

The importance of dropping endorsed payments becomes apparent when we look at how this mitigation defends against a sink attack. The figure below shows the forwarding decisions made by the target node for HTLCs sent to the attacker when we ran the sink attack on our test network with bidirectional reputation implemented.

When the attacker starts to hold HTLCs, its outgoing reputation will drop because in-flight HTLCs reduce reputation. The target node then starts to drop endorsed payments to the attacker, because the attacker no longer has a good reputation. It will still forward unendorsed payments to the attacker, as they represent no risk to its reputation or resources. In our experiment, the target node did not suffer revenue loss - the revenue from the attacker-created cheap paths offsets any loss from the jamming attack, and the attacker is cut off from any endorsed HTLCs thereafter.

Please note that we ran out of time to more rigorously test this out before the summit, so take this all with the “we ran it twice” grain of salt it deserves!

Change Summary

The introduction of bidirectional reputation adds a new component to our original proposal. It’s not much more code, and a POC implementation is available here. The decision tree for the reputation system is outlined below:

if incoming htlc endorsed:

if good incoming reputation and good outgoing reputation:

forward endorsed

elif bad outgoing reputation:

drop payment

else:

forward unendorsed (as below)

else:

if general resources available:

forward unendorsed

else:

drop payment, no resources

Up Next

Our next steps will be to run a more complete set of experiments to test bidirectional reputation as a mitigation against sink attacks, and to re-run our jamming experiments above to ensure that there are no regressions [8]. We’re interested in hearing thoughts on this approach from other protocol developers [9], so please let us know what you think!

This is a difficult problem to solve, and it will require hard tradeoffs, but we’re happy with the mitigation’s performance against resource jamming attacks and optimistic about bidirectional reputation’s ability to mitigate downstream sink attacks.

We’d also like to express our heartfelt gratitude to all that made the trip to attend the attackathon. This work immensely benefited from a wider range of perspectives looking at this problem, and is far better for it!

Footnotes

[0] We only consider economic value that is observable within the protocol (forwarding fees) when we consider the impact of an attack. Users that value their ability to forward payments beyond fees, such as the value of doing business as a lightning service, should be able to specify this exogenous value as an input to the reputation algorithm.

[1] Reputation was implemented via circuitbreaker, which allowed us to quickly implement and iterate on a library with the full reputation algorithm rather than making it LND-specific. Unconditional fees were not implemented in LND, but they are accounted for in our analysis scripts.

[2] This is something we’d potentially look into decreasing (relating this cost to the actual traffic on the channel) if we get some real world numbers indicating that this amount is too steep for honest actors. In that case, we’d expect to come closer to breaking even.

[3] If we remove the requirement that the targeted node can get at least a $1 HTLC endorsed, then we see some cases where an attacker can save around 5% of their costs by performing a laddering attack against a target node that’s barely crossed the reputation threshold.

[4] Attributable errors allow sending nodes to attribute time delays to nodes along the route, which opens the door to latency-sensitive routing algorithms that could route around these malicious sinks.

[5] It’s again tempting to think about monetary solutions here, but these will become prohibitively expensive for honest users to account for the worst-case hold time.

[6] While we assume the attacker can attract some traffic, we do not expect the consistent thundering herd of payments required for a fast jamming attack.

[7] Previously our algorithm only accounted for the risk that an attacker A is targeting outgoing channel BC. By examining reputation in both directions, we can also account for the risk that an attacker B is targeting incoming channel AB.

[7] It’s likely that nodes would not endorse by default anyway, because the upside of successful endorsed/unendorsed payments is the same and endorsed payments pose a risk to their reputation. By only endorsing on failure, sending nodes only take advantage of protected resources when they need to.

[8] We don’t expect any, if anything it’ll make these attacks harder as well, but will repeat for completeness. We wanted to get this post out before the summit, and ran out of time to repeat them!

[9] As is the case with all bitcoin problems, this has already been discussed on the mailing list before our time, so we’re particularly interested in hearing about any conversations that happened off-mailing-list back then!