Mutation testing is a software testing technique used to evaluate the effectiveness of a test suite by intentionally introducing small, systematic faults—called mutants—into the program’s source code, such as changing operators, constants, or conditional logic, and then running the existing tests to see whether they detect these changes. If a test fails, the mutant is considered killed, indicating the tests are sensitive to that kind of fault; if it passes, the mutant survives, revealing a potential weakness or gap in test coverage.

What do we currently do in Bitcoin Core?

Currently, we have a weekly mutation testing run based on the master branch. It means that every Friday, we fetch the code from the master branch, generate the mutants, analyze them by running the unit, functional, and fuzz testing, and generate a report that is shown at https:// corecheck.dev/mutation.

Mutation testing is expensive, because for every mutant we have to: 1. Compile the code, 2. Run the tests, and to be honest, compiling the code is not a considerable problem since we can have a cache, and there is a way to apply the mutations directly in the binary. The main issue is the time we take to run the tests, especially the functional ones. Currently, we have some functional tests that take over 1 minute to run. It means that if we have 20 mutants to analyze, it will take - AT LEAST - 20 minutes. That said, this is the reason I did not start to run it for the whole codebase, only for a set of files that we evaluated as more important to start with.

In general, these runs have been great. We basically have a great overview at corecheck - Test Coverage on what we should improve in our tests, and, gracefully, some PRs have been opened to address some reported mutants. Nowadays, my main goal is to make these runs more and more efficient (which means faster because it takes over 30 hours to run on our current setup), it includes:

- Generate very productive mutants - avoiding spending time with what does not matter (e.g., equivalent or redundant mutants).

- Improving some functional tests to be faster and running exactly what is required to test that mutant.

- We can skip running the weekly mutation analysis for a specific file if no changes were made in that file or in the tests that we use to analyze it.

- Skip generating mutants for lines that do not have any test coverage.

Incremental mutation testing

During the last months, I’ve been trying to run incremental mutation testing using some personal servers. Incremental mutation testing is a technique that applies mutation testing selectively and progressively, rather than re-mutating and re-testing the entire codebase on every run. Instead of generating mutants for all files, it focuses only on the parts of the code that have changed since the last analysis (for example, in a new commit or pull request) and reuses previous mutation results for unchanged code. By caching mutant outcomes and recomputing mutations only where edits or affected dependencies exist, incremental mutation testing drastically reduces execution time and computational cost, making mutation testing practical for continuous integration workflows while still preserving its ability to assess the effectiveness of tests in detecting faults introduced by recent changes.

I selected some PRs and tried to approach incremental mutation testing using the bcore-mutation tool, which has a feature that you can specify a PR number, and it will fetch it and generate the mutants based on the files and lines of code touched by that PR. Also, this tool allows for generating mutants only for lines that contain test coverage.

The problem with this approach is the common problem of mutation testing: time. If an analysis takes hours to run, it would be unfeasible and not useful to evaluate a pull request. Can you imagine someone opening a PR and having to wait hours and hours to receive feedback? Not good!

Thinking about optimizing it, I figured out a paper from Google where they describe how they apply mutation testing on their workflow (which means much, much, much more PRs per day, lines of code, different programming languages, and software engineers than we have).

In general, we have two kinds of “bad” mutants. The equivalent mutant and the unproductive one. The equivalent mutant is a mutant generated during mutation testing that, despite being syntactically different from the original program, is semantically identical—meaning it behaves the same for all possible inputs. Because of this, no test case can ever distinguish it from the original program, so it can never be “killed.” Equivalent mutants are problematic because they artificially lower the mutation score and require manual analysis or heuristic detection to identify, since determining program equivalence in general is undecidable. The unproductive mutant is basically a mutant that is not worth killing. This kind of mutant is harder to detect and requires more manual effort. Google avoids this kind of mutant by collecting feedback from the developers about the mutants and using this feedback to improve the way they generate the mutants. They operationalize this via “arid” AST nodes/lines: places where mutations tend to produce unhelpful results. This strategy, after years, is enough to make them generate better mutants.

Another case they had to discuss was: should we report all the unkilled mutants? I mean, supposing we applied mutation testing for a specific PR, and the analysis resulted in 100 unkilled mutants, should we report all of them to the author? The answer is: No, we should not.

Google does not report all of them as well; they follow a guideline of only reporting 7 mutants, which is a number that came after years of research - and I won’t go deep on this number in this post. What matters here is that we should not spam the PRs with many mutants. In my experience, if a PR has a very low mutation score, probably the tests are not good at all (even the PR), and we should not spend time (doing mutation testing) on it.

My experience doing incremental mutation testing on Bitcoin Core

During the last months, I chose some PRs to analyze them using incremental mutation testing (using the bcore-mutation tool). I tried to follow the least invasive approach possible because, since I would report the mutants in the PR itself, I did not want to spam the PR with many mutants. In general, I followed the number used by Google’s engineers - reporting at most 7 unkilled mutants. Besides that, I spent a lot of time analyzing the unkilled mutants before reporting them because I wanted to make sure they are not “equivalent” or “unproductive”, and, when possible, I tried to report a mutant and a unit or functional test to be addressed and then kill it.

Another manual effort I had was choosing which tests should be run given a touched file. For example, if a PR changes something in src/wallet/coinselection.cpp, I know we can analyze it by running the coinselection_tests/coinselector_tests/spend_tests unit tests, wallet_fundrawtransaction.py functional test and the coin selection fuzz targets. However, it still requires some manual effort to decide since running all of them would be very expensive.

I did it for 8 different PRs:

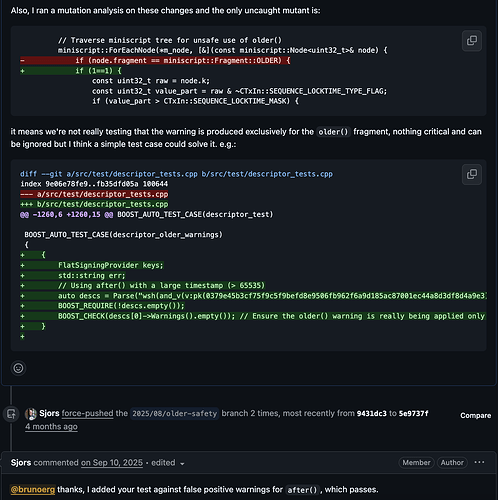

- wallet: warn against accidental unsafe older() import - #33135

- Cluster mempool - #33629

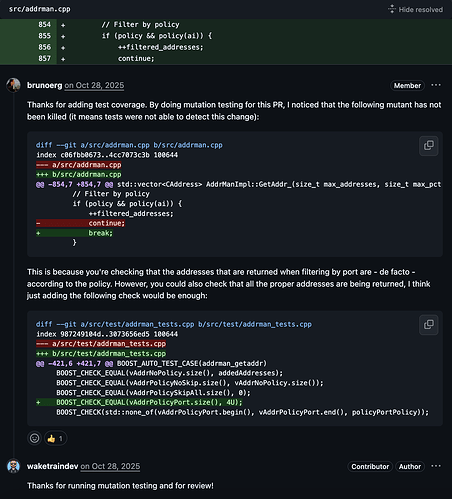

- net: Filter addrman during address selection via AddrPolicy to avoid underfill - #33663

- mining: add getMemoryLoad() and track template non-mempool memory footprint - #33922

- p2p: saturate LocalServiceInfo::nScore to prevent overflow - #34028

- Implementation of SwiftSync - #34004

- Replace cluster linearization algorithm with SFL - #32545

- fuzz: Add tests for CCoinControl methods - #34026

For the PRs #33135, #33663, #33922, and #34026, I reported exactly one mutant, and all the authors gave positive feedback and addressed it. For some of them, I reported the mutant and together suggested a unit test to be addressed. See:

For the PR #32545 (Replace cluster linearization algorithm with SFL), I ran it for the src/cluster_linearize.h file which generated over 200 mutants. To analyze all of these mutants, I ran the cluster_linearize_tests unit test, mempool_packages functional test and the clusterlin_sfl fuzz target. Overall, the mutation analysis showed that the tests are excellent, achieving a mutation rate of 100%, especially due to how the fuzz target was written. I ended up reporting only one mutant, for which the author clarified that the behavior was expected, so it is unkillable anyway.

Even when the PR achieves over 90% or even 100% of mutation score, I like to report it in the PR to advise the reviewers and the author about the confidence and quality of the written tests.

Using mutation testing to evaluate a fuzz target

In September 2025, I published a (peer-reviewed) paper entitled “An empirical evaluation of fuzz targets using mutation testing.” The motivation for this work was the fact that many articles point out that fuzzing is bad for killing mutants. In a way, I agree, because we cannot write harnesses that can assert and handle the large number of inputs that the fuzzer will generate. The goal of fuzz testing is not the same as a unit test. In that paper, I conducted a systematic study using Bitcoin Core as the subject system, analyzing 10 different fuzz targets across various modules and evaluating their ability to detect 726 generated mutants. The methodology involved executing fuzz targets with existing seed corpora and measuring mutation scores both with and without assertion statements to understand the role of explicit oracles in fault detection. Our findings revealed that, contrary to previous studies suggesting fuzzing’s limited effectiveness in mutation testing, several fuzz targets achieved high mutation scores, with two targets reaching 100% mutant detection rates. In general, the ability of the fuzz target to kill mutants (find logical bugs) depends on how the harness is written.

That said, it is expected that if someone is willing to improve a fuzz target, not necessarily covering more code, but adding metamorphic relations, round-trip assertions, etc, that target should be able to find more bugs than before, which means that target is expected to kill more mutants.

One example we recently had on Bitcoin Core is a PR that improves the coin_control target. The author added more assertions to the target, for example, testing that for every outpoint returned by ListSelected is also being pointed as selected on the IsSelected function. This kind of improvement in a fuzz target is expected to make it kill more mutants than before. So I did a mutation testing analysis for wallet/coincontrol.cpp and verified that the mutation score went from less then 25% on the master branch to over 80% on that PR. Also, I left a comment with a suggestion to improve the target that could kill the remaining mutant. So this is an example of the utility of mutation testing for this kind of case.

Final notes - for Core contributors, feedback needed.

- If you want a mutation testing run on any PR, please ping me in the PR.

- Give feedback about the mutants reported in a PR. Even if a mutant does not make sense/is unproductive, tell it. I use the feedback to improve the tool and generate better and better mutants on next runs.

- Should we put the mutants of a PR at corecheck, or is it fine to comment them in the PR? I like the idea of having it at corecheck, but since I really need feedback at this moment, I think I would have more of it in the PR. So, short-term in PR and medium-term move to corecheck?