How OP_CAT enables post-quantum security while preserving Bitcoin’s design principles

Introduction: Quantum Risk as a Bitcoin Engineering Question

At a very simple level, Bitcoin security relies on a kind of mathematical lock. Today, creating a Bitcoin signature is easy if you know the private key, but effectively impossible if you only see the public key. The gap between “easy” and “impossible” is what keeps coins safe.

Under the hood, this lock is built using elliptic curve cryptography. An elliptic curve is a specific mathematical structure where adding a point to itself repeatedly follows simple rules in one direction, but is extremely hard to reverse. In Bitcoin, a private key is just a very large number. The corresponding public key is generated by multiplying that number by a fixed point on the curve. This operation is fast and deterministic. Going backwards — recovering the private key from the public key — requires solving what is known as the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem, which classical computers cannot do efficiently.

Classical computers approach problems step by step, trying possibilities sequentially or with limited parallelism. Even with massive computing power, reversing Bitcoin’s elliptic curve operation by brute force would take longer than the age of the universe. This asymmetry is exactly why elliptic-curve signatures are practical and secure today.

Quantum computers work very differently. Instead of operating on bits that are either zero or one, they operate on quantum states that can represent many possibilities at once. Carefully designed, quantum computers are extraordinarily powerful for certain classes of mathematical problems.

One such problem is the discrete logarithm problem. Shor’s algorithm, a quantum algorithm discovered in the 1990s, can exploit the algebraic structure of elliptic curves to solve this problem efficiently. Where a classical computer must grind through an infeasible search space, a sufficiently powerful quantum computer can extract the private key directly from the public key.

In practical terms, this means that once a Bitcoin public key is revealed on-chain, a future quantum adversary could, in principle, compute the corresponding private key fast enough to steal the coins. This does not break Bitcoin overnight, and it does not affect coins whose public keys have never been exposed¹. But it does mean that Bitcoin’s current signature scheme relies on an assumption — that elliptic curve discrete logarithms are hard — that does not hold in a world with large-scale quantum computers.

The precise timeline for such machines remains uncertain, and estimates vary widely. What matters for Bitcoin is not predicting the exact year, but recognizing that cryptographic transitions operate on much longer timescales than hardware development.

What is important here is not that elliptic curves are “bad,” but that they represent a specific cryptographic assumption. Bitcoin’s signature rules implicitly assume that reversing elliptic-curve point multiplication is infeasible. Quantum computing challenges that assumption directly, not by gradual weakening, but by changing the class of problems that can be solved efficiently.

This creates a subtle but crucial requirement for Bitcoin’s evolution. Bitcoin does not merely need a stronger signature algorithm; it needs a way to express alternative spending conditions without repeatedly redefining consensus around whichever cryptographic construction is currently favored. In other words, the challenge is less about choosing the “right” post-quantum signature today, and more about ensuring that Bitcoin Script is flexible enough to support different constructions as cryptographic understanding evolves.

Seen this way, quantum risk is not a speculative fear but an engineering constraint. Bitcoin must eventually support spending conditions that do not rely on elliptic-curve assumptions alone, while preserving the system’s core properties: simplicity, decentralization, and long-term stability.

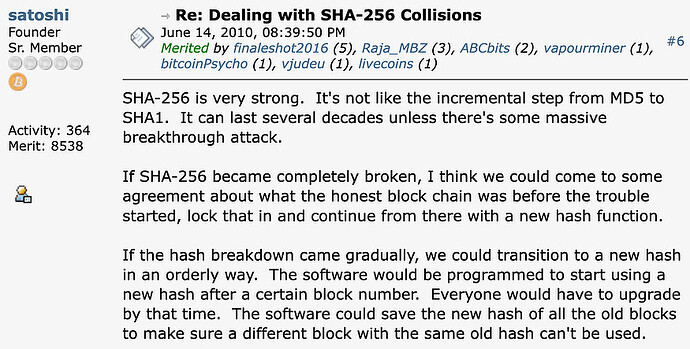

This perspective is not new. As Satoshi Nakamoto noted early in Bitcoin’s history:

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Satoshi was also explicitly aware of quantum computing as a future threat to public-key cryptography, and addressed it directly rather than dismissing it. In discussing quantum computers, he wrote:

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Taken together, these comments show that Bitcoin’s cryptographic assumptions were never meant to be permanent. Both hashing algorithms and signature schemes were understood by Satoshi as replaceable components, with the expectation that advances — whether classical or quantum — would eventually require adaptation.

Discussions about quantum computing and Bitcoin often drift toward abstraction, either dismissing the issue as too distant to matter or framing it as an existential emergency. Both miss the practical question Bitcoin developers actually face: how should a long-lived, bearer asset system plan for cryptographic transitions measured in decades rather than product cycles?

Bitcoin’s security rests on specific cryptographic assumptions that are deliberately conservative. Those assumptions have aged well so far. But unlike most software systems, Bitcoin cannot rely on frequent upgrades or forced migrations. Coins can sit untouched for decades. Outputs created today may still be spendable far into a future where cryptographic capabilities look very different.

Quantum computing does not present an immediate crisis, but it does present a planning problem. Credible estimates suggest that quantum systems capable of threatening elliptic-curve cryptography could emerge within a 5–10 year horizon. That is far enough away to avoid panic, yet close enough that design choices made now will matter.

Rather than jumping directly to solutions, it is worth grounding this discussion in how Bitcoin’s cryptography is actually used today, and why even a narrow change in assumptions has outsized implications for a system designed to last indefinitely.

Background: Bitcoin’s Cryptography and the Quantum Threat

Bitcoin’s use of elliptic-curve signatures underpins ownership, authorization, and finality. Once a signature is validated, the network treats that spend as irreversible. This makes the strength of the underlying cryptographic assumption especially important: a break does not degrade security gradually, it invalidates it outright for affected outputs.

Bitcoin already mitigates quantum exposure in limited ways. Public keys are not revealed until spending, and address reuse is discouraged. Still, Bitcoin’s design assumes that some coins will remain unspent for long periods, and that not all users will follow ideal operational behavior. Over a sufficiently long timeline, that assumption becomes fragile.

The problem, therefore, is not whether Bitcoin is broken today, but whether it has enough expressive flexibility to evolve its spending conditions without repeatedly rewriting consensus rules.

Proposed Solutions

Several approaches are commonly proposed for making Bitcoin resilient to a post-elliptic-curve world. Despite surface differences, they ultimately fall into two categories: proposals that standardize on a specific post-quantum construction via new address or output types, and proposals that introduce new opcodes dedicated to post-quantum signature verification.

The first category consists of proposals that define a new address or output type explicitly designed for post-quantum security. A representative example is BIP360, which proposes a new output format that commits to quantum-resistant public keys or commitments, along with new validation rules for spending those outputs. In this model, the network gains first-class awareness of a post-quantum signature scheme at the UTXO level. The advantage is clarity and efficiency: witness formats can be optimized, verification costs are predictable, and wallets have a clear, standardized target to implement. The trade-off is that this approach necessarily standardizes on a particular family of post-quantum algorithms in consensus. Once such an address type is deployed, Bitcoin effectively commits to that cryptographic choice, and replacing it would require another consensus change. Over multi-decade timelines, this makes Bitcoin’s cryptographic assumptions harder to evolve.

The second category involves introducing new opcodes that natively verify post-quantum signatures. Rather than defining a new address format, this approach extends Bitcoin Script with opcodes that validate signatures produced by a specific post-quantum algorithm. Technically, this can be more expressive than address-based approaches, since Script remains the primary vehicle for spending logic. However, the underlying trade-off is similar. An opcode that verifies a particular lattice-based, code-based, or hash-based signature embeds deep assumptions about performance, security margins, and algorithmic longevity directly into consensus. If cryptographic confidence shifts — as history suggests it will — Bitcoin would again face the challenge of deprecating or replacing consensus-critical logic.

OP_CAT does not fit into either category. It does not define a new address type, nor does it introduce a dedicated post-quantum verification opcode. Instead, it restores a general-purpose scripting primitive — concatenation — that allows more complex verification logic to be expressed using existing opcodes. With OP_CAT available, hash-based signature schemes such as Lamport or Winternitz constructions can be implemented directly in Script by composing existing hash functions, conditional checks, and stack operations.

The technical consequence of this approach is that Bitcoin avoids standardizing on any particular post-quantum algorithm at the consensus layer. Scripts can evolve independently of consensus rules, and different constructions can coexist without requiring new opcodes or address formats. The cost is efficiency: script-level constructions are larger and more expensive to verify than native signature opcodes. But those costs are borne only by users who opt in, rather than imposed globally.

Seen this way, the distinction is not between “having” or “not having” post-quantum security, but between prescription and optionality. Address- and opcode-based proposals prescribe a specific cryptographic future at the consensus layer. OP_CAT expands the design space while keeping Bitcoin’s cryptographic commitments minimal.

OP_CAT as a Different Kind of Tool

OP_CAT takes a fundamentally different approach from both address-based and opcode-based post-quantum proposals. Rather than standardizing a specific cryptographic construction in consensus, it restores a general-purpose scripting primitive that allows users to express more complex verification logic themselves. This shifts Bitcoin’s posture from prescription to optionality: consensus remains small and stable, while the design space above it expands.

Minimalism and the Shape of Consensus Changes. From a consensus perspective, OP_CAT is deliberately minimal. It reintroduces a previously existing opcode with simple, well-defined semantics — concatenation — rather than adding new cryptographic verification rules. No new signature algorithm is embedded in consensus, no new address regime is created, and no assumptions are made about which post-quantum construction is “correct.” Crucially, OP_CAT also avoids locking Bitcoin into a premature decision. As time passes, developers and users can experiment with different post-quantum constructions at the script level, observe which designs are practical, secure, and usable in the real world, and learn from those outcomes. That experience can then inform any eventual, more opinionated upgrade if one is ever needed. No other proposal offers this feedback loop: address-based and opcode-based approaches commit Bitcoin to a specific cryptographic choice before the ecosystem has had the chance to learn from lived usage.

Cryptographic Neutrality and Sovereignty. There is also a critical but often overlooked cryptographic neutrality and sovereignty dimension to this debate. Both a dedicated quantum-signature opcode and a new quantum-safe address type implicitly require Bitcoin to standardize on specific post-quantum algorithms, which in practice means adopting U.S. NIST-approved standards such as SPHINCS+, Dilithium, or Falcon. That choice is not globally neutral. China has been explicit about pursuing digital and quantum sovereignty, developing its own cryptographic standards that are incompatible with NIST, and Europe is increasingly moving in the same direction. Hard-coding any particular post-quantum algorithm into Bitcoin consensus would therefore force Bitcoin to pick sides in a geopolitical standards war — fundamentally at odds with Bitcoin’s role as a global, permissionless system. This concern is not hypothetical: in the classical cryptography era, the NIST-designed curve secp256r1 (P-256) has long attracted suspicion due to its unexplained constants and the historical involvement of the NSA, even though no public backdoor has ever been demonstrated. Satoshi was clearly aware of this risk and deliberately chose secp256k1, a curve not designed by NIST and free of unexplained constants.

OP_CAT continues that tradition. It avoids mandating any algorithm or standards body, and instead restores a general-purpose scripting primitive (concatenation) that allows users to construct quantum-resistant schemes, using only cryptographic assumptions Bitcoin already relies on.

Practical Reusable Hash-based One-time Signatures. Hash-based one-time signature schemes such as Lamport and Winternitz have already been implemented in Bitcoin Script using OP_CAT. Because Lamport and related schemes are inherently one-time-use, practical reuse requires committing to many one-time public keys at once, typically by placing them into a Merkle tree and committing only to the Merkle root on-chain. Spending then requires revealing both the one-time signature and the Merkle authentication path. Verifying this structure in Script necessarily involves concatenating hash elements to recompute intermediate nodes and the Merkle root, making OP_CAT essential rather than optional. In this sense, OP_CAT is not merely an optimization, but a foundational building block for making hash-based, post-quantum signatures usable in Bitcoin.

Trade-Offs and Honest Limits. OP_CAT does not make post-quantum security free. Script-level constructions are less efficient than native signature opcodes. Hash-based signatures are larger, witness data grows, and verification costs increase. These are real costs that must be accounted for in policy limits and standardness rules. But they are also localized costs. Only users who opt into post-quantum scripts pay them, and they can evolve those constructions over time without further consensus changes. In this sense, OP_CAT trades some efficiency for long-term adaptability, preserving Bitcoin’s ability to respond to cryptographic change without repeatedly reopening the consensus surface.

Conclusion: Preparedness Without Panic

Bitcoin does not need to “go post-quantum” tomorrow. It does need to avoid painting itself into a corner.

OP_CAT represents a pragmatic middle path. It does not attempt to predict the future of cryptography. It does not impose new address regimes or bless particular algorithms. It quietly restores a small piece of expressive power that allows Bitcoin to adapt when adaptation is actually needed.

Quantum readiness should look like this: boring, incremental, and reversible. OP_CAT fits that mold. It prepares Bitcoin not by declaring an end state, but by keeping the design space open — just enough to respond when the time comes.

[1] Once a public key is revealed on-chain, a quantum adversary could either mount a long-range attack by later deriving private keys from historically exposed public keys and spending any still-unspent outputs, or a short-range attack by racing a transaction at spend time while it is in the mempool.