I have done some work on formalizing the semantic of OP_CHECKCONTRACTVERIFY. I also wrote the first draft BIP and an implementation in bitcoin-core:

Links:

In this post, I will briefly introduce the OP_CCV opcode semantic, then expand and discuss on an its amount-handling logic — an aspect that wasn’t fully explored (and not properly formalized) in my previous posts on the topic. I will make the argument that it provides a convenient and compelling feature set that would be difficult to implement with more ‘atomic’ opcodes.

OP_CHECKCONTRACTVERIFY

I start with a brief intro on OP_CHECKCONTRACTVERIFY, for the sake of making this post self-contained.

in a nutshell: state-carrying UTXOs

OP_CCV enables state-carrying UTXOs: think of a UTXO as a locked box holding data, rules and an amount of coins. When you spend the UTXO, it lets you peek inside your own box (introspect the data), and decide the next box’s rules (program), data and amount.

less in a nutshell

OP_CCV works with P2TR inputs and outputs. It allows comparing the public key of an input.output with:

- a public key that we call the naked key

- …optionally tweaked with the hash of some data

- …optionally taptweaked with the Merkle root of a taproot tree.

Similarly to taproot, tweaking allows to create a commitment to a piece of data inside a public key. Therefore, by using a ‘double’ tweak, one can easily commit to an additional piece of arbitrary data. An equality check of a double tweak with the input’s taproot key is therefore enough to ‘introspect’ the current input’s embedded data (if any), and an equality check with an output’s taproot public key can force both the program (naked key and taptree) and the data of the output to be a desired value.

In combination with an opcode that allows to create a vector commitment (like OP_CAT, OP_PAIRCOMMIT or a hypothetical OP_VECTORCOMMIT opcode), it is of course possible to commit to multiple pieces of data instead of a single one.

While certainly not the only way to only way to implement a dynamic commitment inside a Script, this is the best I could come up with, and has some nice properties.

Pro:

- Fully compatible with taproot. Keypath spending is still available, and cheap.

- No additional burden for nodes; state is committed in the UTXO, not explicitly stored.

- It keeps the program (the taptree) logically separated from the data.

- Spending paths that do not require access to the embedded data (if any) do not pay extra witness bytes because of its presence.

Con:

- Only compatible with P2TR.

- A tweak is computationally more expensive than other approaches

Amount logic

What about amounts? It would be rather unusual to care about the output’s Script, and then sending 0 sats to it. In most cases, you want to also specify how much money goes there.

Therefore, when checking an output, OP_CCV allows a convenient semantic to specify the amount flow in a way that works for most cases. There are three options:

- default: assign to the output the entire unassigned amount of the current input

- deduct: assign to the output the portion of current input’s amount equal to this output’s amount (the rest remain unassigned)

- ignore: only check the output’s Script but not the amount.

An output can be used with the default logic from different inputs, but no output can be used as the target of both a deduct check and a default check, nor multiple deduct checks.

A well formed Script using OP_CCV would use:

- 0 or more

OP_CCVwith the deduct logic, assigning parts of the input amount to some outputs - exactly 1

OP_CCVwith the default logic, assigning the (possibly residual) amount to an(other) output.

This ensures that all the amount of this input is accounted for in the outputs.

Examples

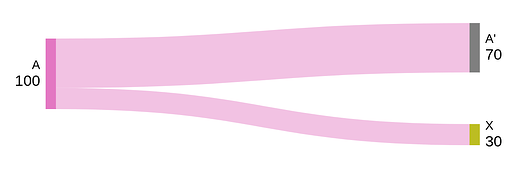

1-to-1

A uses CCV with the default logic to send all its amount to X.

This is common in all the situations where A wants to send the some predefined destination - either e terminal state, or another UTXO with a certain program and data.

In some cases, X might in turn be a copy of A’s program, after updating its embedded data. In this case, A’s Script would first use CCV to inspect the input’s program and data, then compute the new data for the output, then use CCV with the default logic to check the output’s program and data. This allows long-living smart contracts that can update their own state.

many-to-1 (aggregate)

A, B and C uses CCV with the default logic to send all its amount to X.

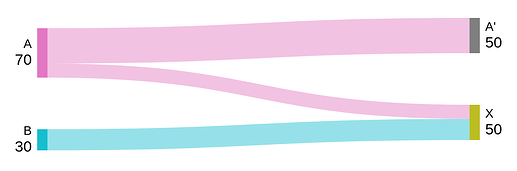

send partial amount

A checks the program and data (if any) of the input using CCV, then it checks that the first input A’ has the same program/data using the deduct logic, then it uses CCV on the second output to send the residual amount to X.

This is used in constructions like vaults, to allow immediate partial revaulting. It could also be used in shared-UTXO schemes, to allow one of the users to withdraw their balance from the UTXO while leaving the rest in the pool (however, this would likely require a CHECKSIG or additional introspection on the exact amount going to X, which CCV alone can’t provide).

(In other application, the partial amount could of course be sent to a completely different program, instead of A’)

send partial amount, and aggregate

A does the same as the previous case, but here a separate input B also sends its amount to X using the default logic, therefore aggregating its amount to the residual amount of A (after deducting the portion going to A’).

Discussion

I’ve been suggested to separate the Script introspection of CCV from the amount logic. That’s a possibility, however:

- you virtually never want to check an output Script without meaningful checks on their amount; so that would be wasteful and arguably less ergonomic.

- both the default and the deduct logic would be very difficult to implement with more atomic introspection opcodes.

Even enabling all the opcodes in the Great Script Restoration wouldn’t be sufficient to easily emulate the amount logic described above. That’s because the nature of these checks is inherently transaction-wide, and can’t be expressed easily (or at all?) with individual input Script checks. Implementing it with a loop over all the involved inputs, it would result in quadratic complexity if every input performs this check. Of course, one could craft a single special input that checks the amount of all the other inputs (which in turn check the presence of the special input), but that’s not quite an ergonomic solution - and to me it just feels wrong.

By incorporating this amount logic where the amount of the input is assigned to the outputs, the actual computations related to the constraint amounts are moved out of the Script interpreter.

I think the two amount behaviors (default and deduct) are very ergonomic, and cover the vast majority of the desirable amount checks in practice. The only extension I can think of is direct equality checks on the output amounts, which could be added with a simple OP_AMOUNT (or OP_INOUT_AMOUNT) opcode that pushes an input/output amount on the stack, or with a more generic introspection opcode like OP_TXHASH).

I implemented fully featured vaults using OP_CCV + OP_CTV that are roughly equivalent to OP_VAULT + OP_VAULT_RECOVER + OP_CTV in the python framework I developed for exploring MATT ideas. Moreover, a reduced-functionality version using just OP_CCV is implemented as a functional test in the bitcoin-core implementation of OP_CCV.

Conclusions

I look forward to your comments on the specifications, implementation, and applications of OP_CHECKCONTRACTVERIFY,