Threshold signatures are now common methods to secure funds in Bitcoin. An m-of-n signature scheme requires at least m signatures to unlock funds secured by n public keys. An open question, however, is the optimal design of such schemes. When should the threshold be high, when should it be low, and how should it change over time? This is where things get interesting. So, we study this problem in a security context, where a malicious attacker tries to steal a user’s signatures.

Imagine you are setting up your wallet. On one hand, a higher threshold keeps attackers at bay - they will need to compromise more keys before they can get your Bitcoin. On the other hand, the higher the threshold, the more likely you are to lock yourself out of your own funds. Self-lockout is a common problem, evidenced by the vast sums that users are willing to pay to recover lost bitcoin.

So, the real challenge is balancing these costs and benefits, namely, the benefit of security against the cost of usability. The “optimal” threshold is the one that minimizes your expected loss. That loss has two parts:

- Attacker Loss: The risk of losing funds to an attacker.

- User Loss: The risk of losing access yourself.

Think of it like this: putting your keys in a safe increases security, while engraving them on a titanium plate improves usability in case of fire. Both strategies give you more room to raise the threshold. At first glance, that might feel counterintuitive since, for example, placing signatures in a safe might induce the user to relax their threshold. But greater security decreases the probability of an attack, thereby making a high threshold relatively cheaper, so the user can afford to adopt a higher threshold than before. In other words, the better your security and usability setup, the more confidently you can raise your threshold and sleep well at night.

To model the security of a threshold signature scheme, let’s call \tau the multi-signature threshold (fraction between 0 and 1). It is the number of required signatures divided by the total. For example, in a 2-of-3 setup, \tau = 2/3. In a 3-of-5, \tau = 3/5. These are common choices in practice.

The value of \tau captures the fundamental trade-off that higher thresholds mean stronger security (since attackers need more keys), but they also raise the chance of locking yourself out.

Now, suppose we define two probabilities:

- p(\tau): the probability that the user controls enough keys to meet the threshold.

- q(\tau): the probability the attacker does.

The specific identities of the signatures are irrelevant; what matters is whether the threshold is met. For instance, in a 3-of-5 scheme, it is irrelevant whether an attacker holds {1,2,4} or {3,4,5}; either set satisfies the threshold.

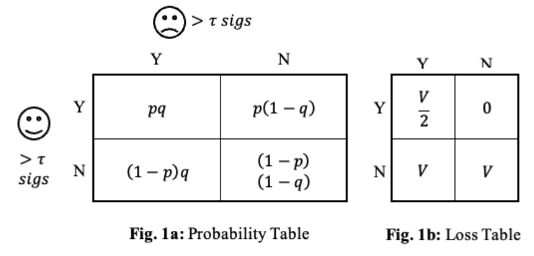

Formally, we can describe the situation with a state space \theta = (\theta_u, \theta_a), where \theta_u = 1 if the user meets \tau and \theta_a = 1 if the attacker meets \tau. That gives us four possible outcomes: {(0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1)}. For simplicity, let’s assume p(\tau) and q(\tau) are independent.

The risk to the user depends on two things: the value of the funds (say V) and who manages to meet the threshold. If only the user meets it, there is no problem. If only the attacker does, the user loses everything. If neither side reaches the threshold, the funds are stuck - still a total loss. And if both do, the outcome is contested, with a 50% chance of losing the funds.

The user will therefore select the threshold to minimize the expected loss across all four states of the world.

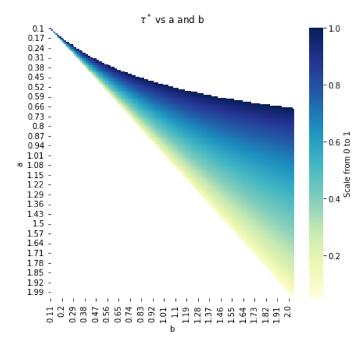

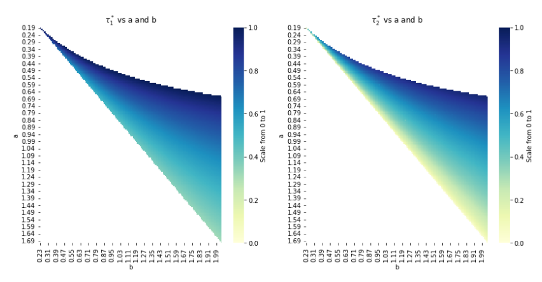

Assuming the probability functions p(\tau) = 1 - \frac{a}{2}\tau^{2} and q(\tau) = 1 - \frac{b}{2}\tau^{2}, we get the closed form solution for optimal threshold signature scheme as

This establishes that the optimal threshold depends on the difference between parameters b and a, which govern the curvature of the attacker’s and user’s probability functions, respectively. Intuitively, the user prefers an environment with:

- High probability of retaining access (high p): This occurs when a is small.

- Low probability of attack (low q): Occurs when b is large.

- Wide gap between b and a: This allows for a higher threshold, improving security and usability.

If the gap between b and a is narrow, the user must choose a lower threshold, which reduces the risk of self-lockout but increases exposure to attacks. The sufficient condition for a positive threshold is b > a, meaning the attacker’s probability function must respond more strongly to changes in the threshold than the user’s.

A core takeaway of this model is that increasing security or usability leads to higher optimal thresholds.

Take a practical example, where moving from a paper wallet to a hardware wallet boosts security. This raises parameter b and supports choosing a higher threshold. On the usability side, engraving seed phrases on a fire-resistant titanium plate reduces parameter a, again making a higher threshold possible.

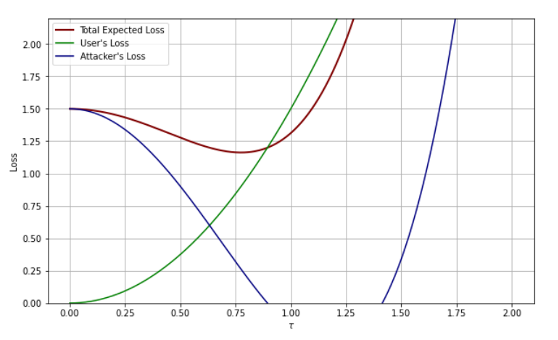

Fig.3 illustrates this trade-off through the loss functions. User loss increases as thresholds rise, since higher thresholds raise the chance of lockout. Attacker loss moves in the opposite direction, falling with higher thresholds because more signatures are required to steal funds. The total expected loss is simply the sum of these two effects.

- Shifts in parameters change the balance: Increasing security (higher b) drives attacker loss lower, reducing overall expected loss and supporting a higher threshold. Increasing a raises user loss instead, pushing total expected loss upward and lowering the optimal threshold.

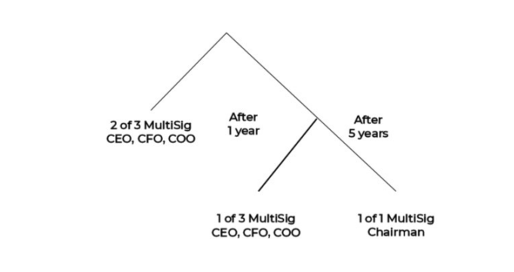

So far, we have focused on static thresholds, but real-world conditions don’t stay constant. Over time, both users and attackers face changing levels of access. To capture this, we develop two dynamic models that show how thresholds can evolve.

Degraded multisignature has a special implementation in Bitcoin that the 2021 Taproot upgrade enabled.

In the first model, both user and attacker access probabilities decay over time. This makes sense because users might lose keys through negligence or hardware failure, while attackers may also lose access as time passes.

This model allows users to set both a threshold and a timelock. The optimal strategy is intuitive:

- Start with higher thresholds in the early stages, when access is fresh and reliable.

- Gradually lower thresholds over time.

- At the same time, extend timelocks, improving both security and usability as the system matures.

Formally, this can be modeled by letting the user’s and attacker’s access probabilities decay exponentially over time (p(\tau)e^{- \lambda t} \ \text{ and } \ q(\tau)e^{- \gamma t}). A degraded multisig scheme is then defined in stages. For each time interval, the scheme specifies a threshold and a corresponding timelock.

The benefit of this approach is that unlike a fixed threshold, a degraded multisig adapts stage by stage, matching the user’s needs and risks over time.

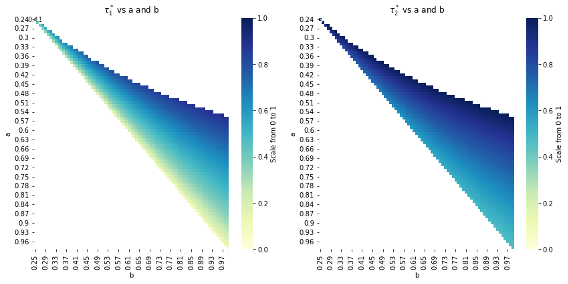

Mathematically, we get the optimal degraded multisig contract as:

where

for\ i = 1,\dots,n.

Key Implications:

- Thresholds degrade over time: early stages use higher thresholds, which gradually decline in later stages.

- Better security or usability allows for higher thresholds and longer time locks.

- As either user access rate (\lambda) or attacker access rate (\gamma) decays faster, the optimal threshold decreases.

The second dynamic model takes a different view, where the user access still decays over time (modeled as p(\tau)e^{- \lambda t}), but the attacker’s access instead increases with frequent signature use (modeled as q(\tau)e^{\gamma t}). Think of it this way - the more signatures are revealed or used, the easier it becomes for an attacker to collect information. In this model, thresholds also tend to decline over time, as users gradually lose keys. But there is a twist: if the attacker’s gain rate grows much faster than the user’s decay rate, the optimal strategy flips. In such cases, thresholds must actually rise in later stages to preserve security. The optimal dynamic threshold signature contract, in this case, is given by:

where

for\ i = 1,\dots,n.

The source code for our simulations is available on Github at: GitHub - sindurasaraswathi/Optimal_Threshold_Signatures

Our analysis here of optimal threshold signature helps to guide some of the wide range of possibilities that Taproot unlocks. Indeed, the Taproot Merkle trees (Taptrees) can have vast depth and complexity, and therefore, some theory is useful in terms of guiding which schemes are superior to others.

Future research can extend this line of work by broadening the economic and security environment of future users of threshold signature schemes. The undiscovered country will be unlocking the full possibility of Taproot to allow for all manner of economic transactions to be represented through Taptrees and more complex contracts, including time locks and multiple signatures. Even greater possibilities will emerge when second-layer protocols integrate with the base layer. This can be particularly useful for artificial agents to utilize the full complexity that Taproot enables. While this work has focused chiefly on the human use cases of threshold signature, future users may be AI agents who can utilize Bitcoin Script in ways we cannot yet imagine.

Read more about this research at: https://www.arxiv.org/pdf/2509.25408