Cluster mempool theory

Transaction graphs and clusters

Definition. A transaction graph, or in cluster mempool context, just graph, is a directed acyclic graph (DAG), with n vertices (also called transactions), where each vertex is labelled with a fee (an integer) and a size (a strictly positive integer). If an edge from node c to node p exists, p is called a parent or dependency of c, and c a child of p. In other words, transaction graphs are dependency graph whose vertices point to their dependencies.

Definition. Given a graph G and a transaction x in it, the ancestor set \operatorname{anc}_G(x) of x is the set of all transactions which can be reached from x (this always includes x itself). For sets S, we define \operatorname{anc}_G(S) = \cup_{x \in S} \operatorname{anc}_G(x), the union of the ancestor sets of all the transactions in the set.

Definition. Given a graph G and a transaction x in it, the descendant set \operatorname{desc}_G(x) of x is the set of all transactions from which x can be reached. For sets S, we define \operatorname{desc}_G(S) = \cup_{x \in S} \operatorname{desc}_G(x), the union of the descendant sets of all the transactions in the set.

Definition. A cluster is a connected component of a graph ignoring direction. In other words, for any two transactions in a cluster it is possible to go from one to the other by making a sequence of steps, each traveling along an edge in either forward or backward direction. The clusters of a graph form a partition of its vertices, and the cluster of a transaction is the connected component which that transaction is part of. It can be found as the transitive closure of the “is parent or child of” relation on the singleton of the given transaction.

Consider the transaction graph below (fees and sizes are omitted):

graph BT

t5["t<sub>5</sub>"] --> t2["t<sub>2</sub>"];

t6["t<sub>6</sub>"] --> t2;

t6 --> t3["t<sub>3</sub>"] --> t1["t<sub>1</sub>"];

t7["t<sub>7</sub>"] --> t4["t<sub>4</sub>"];

In this example there are two clusters: \{t_1, t_2, t_3, t_5, t_6\} and \{t_4, t_7\}.

Definition. Given a subset S of nodes of a graph, define the following functions:

- \operatorname{fee}(S) = \sum_{x \in S} \operatorname{fee}_x: the sum of fees of transactions in S.

- \operatorname{size}(S) = \sum_{x \in S} \operatorname{size}_x: the sum of sizes of transactions in S.

- \operatorname{feerate}(S) = \operatorname{fee}(S) / \operatorname{size}(S): the sum of the fees divided by the sum of the sizes of transactions in S. Only defined for non-empty sets S.

Linearizations and chunks

Definition. A topological subset S of a graph G is a subset of its transactions that includes all ancestors of all its elements. In other words, S is topological subset of G iff \operatorname{anc}_G(S) = S.

Definition. A linearization L for a given graph G is a permutation of its transactions in which parents appear before children. In other words, L = (t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n) is a linearization of G if \{t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_k\} is a topological subset of G for all k = 1 \ldots n. A linearization is thus a topological sort of the graph vertices.

In the example above:

- (t_1, t_2, t_3, t_4, t_5, t_6, t_7) is a valid linearization.

- (t_2, t_5, t_1, t_3, t_6, t_4, t_7) is a valid linearization.

- (t_1, t_3, t_6, t_2, t_5, t_4, t_7) is not (t_6 is included before its parent t_2).

Definition. Given a linearization L for a graph G, and a subset S of G, the sublinearization L[S] is the linearization of S which keeps the same internal ordering as those transactions have in L.

Definition. A chunking C = (c_1, c_2, \ldots, c_n) for a given graph G is a sequence of sets of transactions (called chunks) of G such that:

- The chunks c_i form a partition of G (no overlap, and their union contains all elements).

- Every prefix of chunks is topological (\cup_{i=1}^{k} c_i for k=1 \ldots n are topological subsets of G). Thus, a transaction’s parent can appear in the same chunk as the transaction itself or in an earlier chunk, but not in a later chunk.

- The feerates of the sets are monotonically decreasing.

Note that in practice, we will only work with chunkings of individual clusters, rather than possibly-disconnected graphs. The reasoning for that will come later, so for now, we define chunkings for graphs in general.

Definition. The function \operatorname{chunks}(L) for a linearization L = (t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n) of a graph G returns the corresponding chunking of that linearization, defined as:

- If L (and thus G) is empty, \operatorname{chunks}(L) = ().

- Otherwise:

- Let f_j = \operatorname{feerate}(\{t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_j) for j = 1 \ldots n.

- Let k be the smallest integer \geq 1 such that no f_j > f_k exists.

- Let c = \{t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_k\}.

- \operatorname{chunks}(L) = (c) + \operatorname{chunks}(L[\{t_{k+1}, \ldots n\}]).

In other words, \operatorname{chunks} constructs the chunking of a linearization consisting of successively best remaining prefixes of that linearization.

Theorem. The corresponding chunking \operatorname{chunks}(L) is a valid chunking for G.

Proof. All criteria for a valid chunking are fulfilled:

- All transactions that occurred in L (which are all transactions in G) will appear in \operatorname{chunks}(L) once.

- Every prefix of chunks is topological, because each corresponds to a prefix of L (which are topological for any valid linearization).

- The feerates are monotonically decreasing. If that wasn’t the case, the chosen k would violate the “no f_j > f_k” rule.

Theorem. The feerate of a prefix of a linearization never exceeds its first chunk feerate. If it did, the first chunk would clearly not be the highest-feerate prefix of the linearization.

Theorem. The feerate of a suffix of a linearization is never less than its last chunk feerate. This is true within the last chunk, because if there was a suffix of the last chunk with lower feerate than that chunk, that suffix could be split off, and the feerate of the part before it would go up. It is also true across multiple chunks, because if a suffix can’t have a lower feerate than the last chunk, then extended the suffix to a chunk before it (whose maximum suffix feerate is even higher) cannot change that property.

Definition. We also define a corresponding linearization of a chunking as a linearization consisting of a concatenation of the chunks, in order, and within each chunk ordered topologically. This correspondence is not unique (because there can be multiple topological sorts of the chunk elements), but all corresponding linearizations of a chunking have the original chunking as corresponding chunking (or a strictly better one) Due to the simplicity of converting between chunking and linearization, we can often treat them as the same.

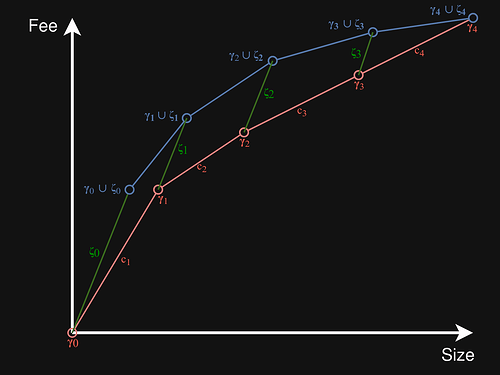

Definition. Given a chunking C = (c_1, c_2, \ldots, c_n), its feerate diagram \operatorname{diag}_C is a real function with domain [0, \operatorname{size}(c_1 \cup c_2 \cup \ldots c_n)], defined as follows:

- Let \gamma_i = \cup_{j=0}^{i} c_j for i=0 \ldots n, the union of all transactions in the first i chunks.

- For all i = 0 \ldots n-1 and \alpha \in [0,1]:

- \operatorname{diag}_C(\operatorname{size}(\gamma_i) + \alpha \operatorname{size}(c_{i+1})) = \operatorname{fee}(\gamma_i) + \alpha \operatorname{fee}(c_{i+1}).

- In other words, \operatorname{diag}_C is a function from cumulative fees to cumulative sizes. When evaluated in the size of a prefix of chunks in C, it gives the fee in that prefix. For other values it linearly interpolates between those points.

- The feerate diagram of a linearization is that of its corresponding chunking.

Theorem. The feerate diagram \operatorname{diag}_L of a linearization L = (t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n) is the minimal concave function for which for every k = 0 \ldots n it holds that \operatorname{diag}_L(\operatorname{size}(\{t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_k\}) \geq \operatorname{fee}(\{t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_k\}). As such, it gives an overestimate for the fees in all prefixes of a linearization. In other words, the grouping of transactions performed by \operatorname{chunks} exactly corresponds to the straight line segments resulting from requiring the feerate diagram to be concave. [no proof]

Definition. We define a preorder on linearizations/chunkings for the same graph G by comparing their feerate diagrams:

- Two linearizations are equivalent if their feerate diagrams coincide: L_1 \sim L_2 \iff \forall x \in [0, \operatorname{size}(G)]: \operatorname{diag}_{L_1}(x) = \operatorname{diag}_{L_2}(x).

- A linearization is at least as good as another if its feerate diagram is never lower than the other’s: L_1 \gtrsim L_2 \iff \forall x \in [0, \operatorname{size}(G)]: \operatorname{diag}_{L_1}(x) \geq \operatorname{diag}_{L_2}(x).

- A linearization is at least as bad as another if its feerate diagram is never higher than the other’s: L_1 \lesssim L_2 \iff \forall x \in [0, \operatorname{size}(G)]: \operatorname{diag}_{L_1}(x) \leq \operatorname{diag}_{L_2}(x).

- A linearization is better than another if its feerate diagram is never lower than the other’s, and at least somewhere higher: L_1 > L_2 \iff L_1 \gtrsim L_2 and not L_1 \sim L_2.

- A linearization is worse than another if its feerate diagram is never higher than the other’s, and at least somewhere lower: L_1 < L_2 \iff L_1 \lesssim L_2 and not L_1 \sim L_2.

- Linearizations L_1 and L_2 are incomparable when neither L_1 \gtrsim L_2 nor L_1 \lesssim L_2 (and comparable when at least one of those relations holds).

- This is not a partial order, because L_1 \sim L_2 does not imply L_1 = L_2 (distinct linearizations can be equivalent).

Transformations on linearizations

Theorem. The chunk reordering theorem: reordering a linearization with changes restricted to a single chunk results leaves it at least as good, provided the result is still a valid linearization (i.e., its prefixes are topological).

Proof. Every prefix of chunks in the original linearization remains a prefix of transactions in the new linearization. Because the new feerate diagram is the minimal concave function not below these points, and these points form the old feerate diagram, the new feerate diagram cannot be below the old one.

Theorem. The prefix stripping theorem: Given two linearizations L_1 = (t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n) and L_2 = (u_1, u_2, \ldots, u_n) for the same graph with a shared prefix: t_i = u_i for all i = 1 \ldots k. In this case:

- If the suffix is at least as good, then the whole linearization is at least as good: (t_{k+1}, t_{k+2}, \ldots, t_n) \gtrsim (u_{k+1}, u_{k+2}, \ldots, u_n) \implies L_1 \gtrsim L_2.

- If the suffix is at least as bad, then the whole linearization is at least as bad: (t_{k+1}, t_{k+2}, \ldots, t_n) \lesssim (u_{k+1}, u_{k+2}, \ldots, u_n) \implies L_1 \lesssim L_2.

Theorem. The gathering theorem. Moving a sublinearization of transactions to the front of a linearization never worsens the linearization if the sublinearization’s worst chunk feerate is at least that of the linearization’s best chunk feerate (see discussion in merging incomparable linearizations):

- Let L be a linearization of a graph G.

- Let C = (c_1, c_2, \ldots, c_n) = \operatorname{chunks}(L).

- Let S be a topologically valid subset of G.

- Let D = (d_1, d_2, \ldots, d_m) = \operatorname{chunks}(L[S]).

- Let L' = L[S] + L[G \setminus S]), the linearization obtained by moving L[S] to the front.

In this case, \operatorname{feerate}(d_m) \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_1) \implies L' \gtrsim L.

Proof.

- Let f = \operatorname{feerate}(c_1), the feerate of the highest-feerate prefix of L.

- Let e_j = c_j \cap S for j=1 \ldots n, the S transactions in chunk j of L. Note that this is distinct from d_j because e_j follows the chunk boundaries of L, while d_j follows the boundaries of L[S].

- Let \gamma_j = \cup_{i=1}^{j} c_i for j=1 \ldots n, the transactions in the first j chunks of L.

- Let \zeta_j = \cup_{i=j+1}^{n} e_i for j = 1 \ldots n, all remaining transactions of S after the first j chunks of L.

- Let P(x) = (\operatorname{size}(x), \operatorname{fee}(x)), the point in 2D space corresponding to the size and fee of set x.

- We know \operatorname{feerate}(c_j) \leq f for j=1 \ldots n, because chunk feerate decrease monotonically.

- We know \operatorname{feerate}(\zeta_j) \geq f for j=0 \ldots n-1, because feerates of the suffix of a linearization (L[S] in this case) are never below the last chunk’s feerate.

- Thus, \operatorname{feerate}(\zeta_j) \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_k) for any j, k where those values are defined.

- Define \operatorname{ndiag}(x) as the real function that linearly interpolates through (0,0) and through all (P(\gamma_j \cup \zeta_j))_{j=0}^{n} (the set of chunk prefixes of $L plus all transactions from S).

- \operatorname{ndiag} is not \operatorname{diag_{L'}}, the feerate diagram of L', because it doesn’t follow the proper chunking of L'. It is however a valid underestimate of it: \forall x \in [0, \operatorname{size}(G)] : \operatorname{ndiag}(x) \leq \operatorname{diag_{L'}}. This is because:

- \operatorname{diag_{L'}} is the minimal concave function through the P points for all prefixes of L'.

- \operatorname{ndiag} is the minimal concave function through the P points for some prefixes of L' (those corresponding to the chunk prefixes of L, plus all transactions of S).

In what follows, we will show that \forall x \in [0,\operatorname{size}(G)]: \operatorname{ndiag}(x) \geq \operatorname{diag_L}(x), and thus by extension that \operatorname{diag_{L'}}(x) \geq \operatorname{diag}(x), or L' \gtrsim L.

In the drawing below, the red line represents \operatorname{diag}_L, while the blue line (plus the green \zeta_0 segment) represents \operatorname{ndiag}. Intuitively, the blue line lies above (or on) the red line everywhere because the slope of every the green \zeta_j segments between red and blue is at least as high as that of any red c_j segment.

\operatorname{diag_L} is a concave function, which means it lies on or below each of its tangents. This implies that a point lies on or above the function iff it lies on or above at least one of its tangents. For every point on \operatorname{ndiag} we will identify a tangent of \operatorname{diag_L} that it lies on or above. As that function is made up of straight segments, its tangents are exactly these segments, extended to infinity in both directions.

- The points \{\forall \alpha \in [0, 1]: \alpha P(\zeta_0)\} lie on the first segment of \operatorname{ndiag}. We show they lie on or above the (extension of the) c_1 segment of \operatorname{diag}(L).

- For \alpha=0, the functions coincide at (0, 0).

- For \alpha > 0, the slope from (0,0) to P(\gamma_1) is \operatorname{feerate}(c_1) = f. The slope of the line from (0,0) to \alpha P(\zeta_0) is \operatorname{feerate}(\zeta_0) \geq f , which is at least as high.

- For i=0 \ldots n-1, the points \{\forall \alpha \in [0, 1]: (1-\alpha)P(\gamma_i \cup \zeta_i) + \alpha P(\gamma_{i+1} \cup \zeta_{i+1})\} lie on \operatorname{ndiag}. We show they lie on or above the (extension of the) c_{i+1} segment of \operatorname{diag}(L).

- The slope of the c_{i+1} segment, from P(\gamma_i) to P(\gamma_{i+1}), is \operatorname{feerate}(c_{i+1}) \leq f.

- For \alpha = 0, the slope of the line from P(\gamma_i) to (1-\alpha)P(\gamma_i \cup \zeta_i) + \alpha P(\gamma_{i+1} \cup \zeta_{i+1}) is \operatorname{feerate}(\zeta_i) \geq f.

- For \alpha = 1, the slope of the line from P(\gamma_i) to (1-\alpha)P(\gamma_i \cup \zeta_i) + \alpha P(\gamma_{i+1} \cup \zeta_{i+1}) is \operatorname{feerate}(\zeta_{i+1} \cup c_{i+1}). Since \operatorname{feerate}(\zeta_{i+1}) \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_{i+1}), it follows that \operatorname{feerate}(\zeta_{i+1} \cup c_{i+1}) \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_{i+1}).

- The one exception is i = n-1, as \zeta_n is empty there, and thus has no \operatorname{feerate}; this is not a problem as the functions coincide in this point.

- The points with 0 < \alpha < 1 linearly interpolate between \alpha=0 and \alpha=1. Since both endpoints lie on or above the segment, the points in between also lie on or above the same segment.

Thus, \operatorname{ndiag}, an underestimate for the feerate diagram of L', is always at least as high as \operatorname{diag_L}, the feerate diagram of L. We conclude that L' \gtrsim L.

Merging linearizations

Definition. Let \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) be the function on graphs G with valid linearizations L_1 and L_2, defined as follows:

- If G (and thus L_1 and L_2) are empty, \operatorname{merge}(\{\}, (), ()) = ().

- Otherwise:

- Let (c_1, \ldots) = \operatorname{chunks}(L_1).

- Let (c_2, \ldots) = \operatorname{chunks}(L_2).

- If \operatorname{feerate}(c_1) > \operatorname{feerate}(c_2), swap L_1 with L_2 (and c_1 with c_2).

- Let L_3 = L_1[c_2], the first chunk of L_2, using the order these transactions have in L_1.

- Let (c_3, \ldots) = \operatorname{chunks}(L_3).

- Let L_4 = L_3[c_3] = L_1[c_3], the linearization of the first chunk of L_3.

- \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) = L_4 + \operatorname{merge}(G \setminus c_3, L_1[G \setminus c_3], L_2[G \setminus c_3]).

Theorem. \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) \gtrsim L_1 and \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) \gtrsim L_2.

Proof.

The theorem is trivially true for empty G. For others, we use induction:

- First note that \operatorname{feerate}(c_3) \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_1):

- After the optional swapping step it must be the case that \operatorname{feerate}(c_2) \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_1).

- Further, \operatorname{feerate}(c_3) \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_2), because L_3 contains the same transactions as c_2. If the \operatorname{chunks} operation on L_3 finds nothing better, it will pick the entirety of L_3 as c_3, which has the same feerate as c_2.

- Now define the following:

- Let L_1' = L_4 + L_1[G \setminus c_3]. By the gathering theorem, L_1' \gtrsim L_1, as it is bringing a topologically valid sublinearization (L_4 = L_1[c_3]) to the front, and it has just a single chunk (c_3), whose feerate is \geq \operatorname{feerate}(c_1), the highest feerate in L_1.

- Let L_2' = L_4 + L_2[G \setminus c_3]. By the chunk reordering them, L_2' \gtrsim L_2, as L_2' equals L_2 apart from its first chunk (c_3 \subset c_2).

- By the induction hypothesis, \operatorname{merge}(G \setminus c_3, L_1[G \setminus c_3], L_2[G \setminus c_3]) \gtrsim L_1[G \setminus c_3], and thus by the stripping theorem, L_4 + \operatorname{merge}(G \setminus c_3, L_1[G \setminus c_3], L_2[G \setminus c_3]) \gtrsim L_4 + L_1[G \setminus c_3] = L_1'. The same reasoning applies to L_2'.

- Put together, \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) \gtrsim L_1' \gtrsim L_1 and \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) \gtrsim L_2' \gtrsim L_2.

Variations. A number of variations on this algorithm are possible which do not break the proof above:

- Whenever a non-empty prefix P is shared by L_1 and L_2, it can be skipped (this follows directly from the stripping theorem), so if L_1 = P + A and L_2 = P + B, then one can define \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) = P + \operatorname{merge}(G \setminus P, A, B).

- Instead of only considering the first chunk of L_2 in the order of L_1, it’s possible to also consider the first chunk of L_1 in the order of L_2, and then pick the first chunk of the one of those two which has the higher feerate.

Optimal linearizations

Definition. An optimal linearization/chunking for a graph is one which sorts higher or equal than every other linearization/chunking for the same graph. Note that this implies that optimal linearizations/chunkings are comparable with every other linearization/chunking. An optimal linearization/chunking is a greatest element of the set of all linearizations/chunkings of a graph.

Theorem. The set of linearizations/chunkings of a graph, with the preorder relation defined above, forms an (upward) directed set.

Proof. From the properties of the \operatorname{merge} algorithm it follows that for any two linearizations L_1 and L_2 there exists a L_3 = \operatorname{merge}(G, L_1, L_2) such that L_3 \gtrsim L_1 and L_3 \gtrsim L_2.

Theorem. Every graph has at least one optimal linearization/chunking.

Proof. In a directed set, every maximal element is a greatest element. Every finite preordered set has at least one maximal element. In a directed set, that element is a greatest element too.

Definition. For a given total ordering R_1 on the set of sets of transactions, and a total ordering R_2 on the set of sequences of transactions, define the function \operatorname{opt}_{R_1,R_2}(G), for a given graph G as follows:

- If G is empty, return the empty sequence: \operatorname{opt}_{R_1,R_2}(G) = ().

- Otherwise:

- Let S be the highest-feerate subset of G. If there are multiple, pick the first one according to R_1.

- Let L_S be the first valid linearization of S according to R_2.

- \operatorname{opt}_{R_1,R_2}(G) = L_S + \operatorname{opt}_{R_1,R_2}(G \setminus S).

Theorem. \operatorname{opt}_{R_1,R_2}(G) is an optimal linearization of G.

Proof. Assume L = \operatorname{opt}_{R_1,R_2}(G) is not an optimal linearization of G. We already know an actual optimal linearization L_{opt} must exist though, so L_{opt} > L.

There must be a first chunk in the chunking of L where the fee-size diagram differs with L_{opt}. Let p be the set of all transactions in L in chunks before that point. Let L_{opt}' = L[p] + L_{opt}[G \setminus p], i.e. the linearization obtained by moving the diagram-equal L chunks to the front in L_{opt}. By repeatedly applying the gathering and stripping theorem, L_{opt}' \gtrsim L_{opt}. Because L_{opt} is optimal this implies L_{opt}' \sim L_{opt} > L. L_{opt}' and L both start with the same chunks, so by removing them we get L_{opt}[G \setminus p] > L[G \setminus p]. L[G \setminus p] = \operatorname{opt}_{R_1,R_2}(G \setminus p) however, and it starts by picking the highest-feerate subset of (G \setminus p), and yet L_{opt}[G \setminus p] starts with a better chunk. This is a contradiction.

For how to compute \operatorname{opt}(G) efficiently, see How to linearize your cluster.

Connected chunks

Definition. A connected chunking is a chunking for which each chunk is connected ignoring direction (i.e., given any transaction in a chunk, every other transaction in the same chunk can be reached when ignoring direction of the edges).

Theorem. In an optimal linearization/chunking, the corresponding chunks have connected components whose feerate is all the same. This is trivially true if the chunks are all connected.

Proof If not, the chunks could be split in two, which would improve the diagram.

Theorem. Every graph has at least one optimal linearization/chunking whose chunks are connected.