Spanning-forest cluster linearization

This is a write-up about a work in progress cluster linearization algorithm that appeared (and may still be) promising as a replacement for the ones described in the currently-implemented algorithms (Bitcoin Core PRs 30126, 30285, 30286 and Delving posts on linearization and related algorithms).

While this spanning-forest algorithm looks promising, the recent discovery by @stefanwouldgo that well-known minimal-cut-based algorithms with good asymptotic complexity exist for the problem we call cluster linearization (the established term is the “maximum-ratio closure problem”) is even more promising.

I am still creating this write-up, because despite lacking known complexity bounds, it appears to be very elegant, fast, and practical (I have a prototype implementation. It is possible that good bounds for it still get found, or that its insights help others build on top, or that it ultimately appears more practical for the real-life problems we face than more advanced algorithms. Or perhaps we discover it’s actually equivalent to a well-known algorithm. I don’t know, but before switching over to studying another approach, I want to have it written down in some form, also to have my own thoughts ordered.

1. Background: cluster linearization as an LP problem

(Skip this section if you’re not interested in the background that led to this idea)

Cluster linearization can be done by repeatedly finding the highest-feerate topologically-valid subset, moving it to the front of a linearization, and then continuing with what remains of a cluster. This reduces the problem of optimal linearization to the problem of finding the highest-feerate topologically-valid subset. This problem can be formulated as a linear programming problem (credit to Dongning Guo and Aviv Zohar):

- For every transaction i, have a variable t_i \in \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}. t_i > 0 means including transaction i in the solution set; t_i = 0 means not including it. Using real numbers instead of booleans here may seem strange, but it will turn out that all non-zero t_i will have the same value anyway.

- Enforce the topology constraints by adding an inequality per dependency: for each parent-child pair (p,c), require t_p \geq t_c. Thus, if a child is included (nonzero), so is the parent.

- Use as goal function g = \sum_i t_i \operatorname{fee}(i) / \sum_i t_i \operatorname{size}(i), which is the feerate of the solution set. It doesn’t matter that the non-zero t_i may take on values different from 1, because they contribute equally to numerator and denominator anyway, meaning that multiplying all of them with the same value has no effect.

- To make the goal function linear (it is a fraction so far), add one additional normalization constraint that the numerator is 1: \sum_i t_i \operatorname{size}(i) = 1, and thus the goal becomes just g = \sum_i t_i \operatorname{fee}(i).

It can be proven that any optimal solution to this problem is an optimal solution to the “find highest-feerate topologically-valid subset” problem.

This immediately has two implications:

- Cluster linearization can be done in worst-case polynomial time, through polynomial-time LP solving algorithms, including ones based on Interior Point Methods. These are not necessarily the best approach for our problem, but their existence conclusively settles the fact that the problem is not NP-hard for example.

- The entire scientific domain of linear programming solution techniques becomes applicable to our problem.

1.1. The simplex algorithm for finding high-feerate sets.

Probably the best-known, and in some variation, most commonly used algorithm for solving linear programming problems is the simplex algorithm.

Internally, the simplex algorithm requires that the problem, and the goal, be stated as equations over a number of non-negative real variables, with no inequalities besides non-negativity. Our t_i variables are already non-negative, but we have inequalities left. We can introduce slack variables to get rid of those:

- Introduce a d_j \in \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} for every dependency (p_j, c_j): d_j = t_{p_j} - t_{c_j}, replacing the dependency inequalities.

In a problem with n transactions and m dependencies, this means n + m + 1 variables (t_{1 \ldots n}, d_{1 \ldots m}, and g), and m + 2 equations:

- d_j = t_{p_j} - t_{c_j}, for j = 1 \ldots m (the dependencies)

- g = \sum_i t_i \operatorname{fee}(i) (the goal)

- \sum_i t_i \operatorname{size}(i) = 1 (the normalization)

The simplex algorithm then maintains a set of n-1 free variables, which are chosen to be zero. All other variables (the basic variables) can be computed from the free variables using the m+2 equations. In every iteration of the algorithm, one free variable is chosen to become basic, while a basic algorithm is chosen to become free. In this context:

- A free t_i variable means transaction i is excluded from the solution.

- A free d_j variable means that transactions p_j and c_j are either both included, or both excluded.

There are rules that control which variables are picked to become free/basic, which generally boil down to not worsening the existing solution, and keeping the solution valid. In addition, various policies exist that attempt to maximize progress in every step.

1.2. Interpreting simplex steps in our problem space

Note that groups of transactions can exist that are reachable from one another through free d_j variables, and thus they must all be included in the solution set, or all excluded from it. Let’s call these groups “chunks”, for reasons that will become clear later.

Because of further rules on the choices taken by the simplex algorithm, further properties hold:

- No “cycle” of free d_j variables can exist within a chunk (because at least one d_j = 0 would be redundant).

- Within every chunk, there can at most be 1 free t_i variable (a second one would be redundant).

- By a counting argument (exactly n-1 free variables) it follows that all chunks, except for one, will contain a free t_i variable, and thus be excluded.

Overall this means that every state of the simplex algorithm corresponds to a partitioning of the transaction graph into chunks, each of which is connected internally by a spanning tree (because no cycles) of free d_j variables, and among them one is the solution set. In every iteration of the algorithm:

- One free variable is made basic, which is either:

- A t_i variable: an excluded chunk whose feerate is higher than the included chunk’s feerate is made not-excluded. It may become included, or end up being merged with another (included or excluded) chunk, see below.

- A d_j variable: a chunk breaks apart into two chunks, as the dependency between them is made basic (in a spanning tree, removing any link breaks the tree in two), where the “top” chunk (the one containing the parent of the d_j variable) has higher feerate than the included chunk, or the “bottom” chunk has lower feerate than the included chunk.

- One basic variable is made free, which is either:

- A t_i variable: the previously-included chunk is made excluded, if the chunk made non-excluded or split off above has no (basic) dependencies on another chunk (i.e., it is topological).

- A d_j variable otherwise: the non-excluded or newly-split off chunk merges with another chunk it depends on.

1.3. From high-feerate subsets to full linearization

There appear to be several superfluous details to the algorithm above. It keeps track of (up to) one specific free t_i variable within each chunk, but the choice of which transaction i that is for each excluded chunk is almost entirely irrelevant to the algorithm. Furthermore, one can wonder what the point is of having to keep track of which chunk is included explicitly, as it will always just be the highest-feerate one among the chunks. We choose to make a few simplifications to the algorithm:

- Get rid of the t_i variables. The included chunk is implicitly the one with the highest-feerate; the rest is excluded.

- Avoid comparing with the chunk feerate of the included set:

- To determine which d_j to make basic, do not compare the top or bottom would-be chunk with the included chunk, but with each other. The rule becomes that one can split a chunk in two along a dependency, if doing so results in a top chunk with higher feerate than the bottom one.

- A d_j variable can be made free if the chunk the child is in has a higher feerate than the top chunk (i.e., merging a chunk with a parent if it is not topological).

- By doing this, we’re effectively not just optimizing the included chunk, but all chunks. And this is why they’re called chunks: they become the chunks of the full linearization when the algorithm ends, with credit to @murch for noting the similarity between the algorithm and the chunking algorithm.

Thus, overall, we obtain an algorithm whose state is a spanning forest (a collection of spanning trees covering the whole graph) for the overall cluster, and which aims to find the overall linearization of the whole thing, not just the first chunk.

2. The algorithm

Restated from scratch, without the whole LP/Simplex background that led to it, the spanning forest linearization algorithm is:

- Input:

- A transaction graph for a cluster, with fees, sizes, and dependencies between the transactions.

- Output:

- An optimal linearization for the graph.

- State:

- For every dependency in the graph, maintain a boolean, “active”. Initially all dependencies are inactive (active dependency corresponds to “free d_j” in the previous section, but “active” seems like a more appropriate name when dropping the simplex context).

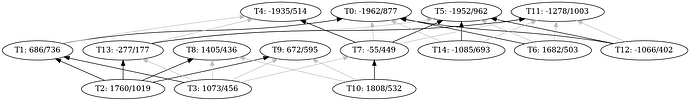

- The set of active dependencies implicitly partition the graph into chunks. Two transactions are in the same chunk if there is a path of active dependencies (each in either the parent-of or child-of direction) from one to another. If there is no such path, the transactions are in different chunks. This means that the initial state is every transaction in its own singleton chunk.

- An invariant of the algorithm is that no cycles can exist within the active dependencies (again, ignoring direction). In other words, the active dependencies within each chunk form a spanning tree, and the active dependencies for the entire cluster form a spanning forest for it.

- Algorithm:

- Perform one of these permitted steps as long as any apply:

- Merging chunks. If there is an inactive dependency, where the parent and child are in distinct chunks, and the child chunk has higher feerate than the parent chunk, make the dependency active, merging the two chunks.

- Splitting chunks. If there is an active dependency, consider the two chunks that would be created by making it inactive (due to the spanning-forest property, this is the case for every active dependency). If the would-be chunk with the parent of the dependency in has a higher feerate than the child chunk, make the dependency inactive, splitting the chunk in two.

- Output the final chunks, sorted from high feerate to low feerate, tie-breaking by topology, each chunk internally sorted by an arbitrary for valid topological order (e.g., by increasing number of ancestors).

- Perform one of these permitted steps as long as any apply:

2.1. Correctness

Since several changes were made to the simplex algorithm along the way to obtain the spanning forest algorithm, it is not necessarily the case anymore that it is correct.

The algorithm above, if it terminates, outputs an optimal linearization, or put otherwise: the successively output chunks are each a highest-feerate topological subset of what remains of the cluster. The theory thread proves that this suffices for an optimal linearization. To see the output chunks are optimal:

- There cannot be any higher-feerate chunk that depends on a lower-feerate chunk, because if there was, the chunk merging rule above would still apply, and the algorithm has not terminated. Thus, the chunks that come out, from high feerate to low feeate, form a valid linearization.

- As for optimality, it holds that the highest-feerate chunk is actually the highest-feerate topologically-valid subset of the active subgraph of the cluster. Since fewer dependencies means fewer constraints, the highest-feerate set for just the active subgraph is certainly no worse than the highest-feerate set for the actual, more constrained, problem. To see why the highest-feerate chunk is the highest-feerate topologically-valid subset of the active subgraph:

- It is certainly topologically-valid, because it is topologically-valid for the actual problem (see above).

- Imagine a higher-feerate topologically-valid subset of the active subgraph existed. Consider its intersections with the final chunks in the algorithm. At least one of those must have a feerate above the highest-feerate chunk itself (if not, their combined feerate, which is a weighted average, would not be higher either). That intersection must be obtainable by cutting off certain branches of the spanning tree, and some of those branches must have a feerate lower than the chunk feerate (otherwise cutting them off would not be an improvement). However, because the splitting rule of the algorithm is not applicable (or the algorithm wouldn’t have terminated), no such branch can exist (if it did, the chunk would have been split in two right there).

- All the properties above remain valid after the highest-feerate chunk is removed from the graph, which is exactly the state obtained before the next chunk is output.

Note that all of these properties are conditional on the assumption that the algorithm terminates. It is less clear under what conditions that is the case (see below).

2.2. Refining the merge and split choices

So far, we have left unspecified which dependencies are to be made active/inactive. From casual fuzzing, it appears that just making random choices is sufficient to obtain the optimal result, but random choices can result in repeated states, which means it can include pointless work which we’d like to avoid.

Thanks to @ajtowns and @ClaraShk for the discussions that led to the conclusions in this section.

2.2.1. Prioritize merge over split

One easy refinement, which will simplify further analysis, is to prioritize merging over splitting. The idea is that merging is making the state topological, while splitting is about making the state better. If we, after every improving split step, perform merges as long as possible, we make the state topological as soon as possible again. This has the practical advantage that if we want to stop the algorithm (due to running out of time), we end up with something that’s at least valid.

2.2.2. Merge by highest feerate difference

When performing merges, there may be multiple inactive dependencies where the child chunk has a higher feerate than the parent, in which case it is unclear which one to pick. From casual fuzzing, it appears that prioritizing the one where the feerate difference between the child and parent is maximal has a number of advantages:

- The same state is never repeated, which - if true - must imply that some (possibly minute) strict improvement happens every iteration.

- It appears to be a good choice for minimizing the number of iterations needed in the worst case.

Furthermore, it simplifies reasoning about termination. Call an “improvement step” to be one application of the splitting rule (using whatever criterion to select which one), followed by as many applications of the merging rule (using maximum feerate difference first as selection strategy) as possible. If the state was topological (= no merge steps applicable) before an improvement step, we can compare the feerate diagrams of the linearizations that would be output before and after the improvement step.

Think of the state of the chunks implicitly as an ordered list, from higher-feerate to lower-feerate, plus the fact that chunks can only depend on chunks that come before it. When a split happens, there are two possibilities:

- The higher-feerate split-off chunk (the parent chunk) depends (through another inactive dependency) on the lower-feerate one (the child chunk). Since the produced child has lower feerate than any other chunk it may depend on, the maximum-feerate-difference rule in this case says that it must merge with itself again, even if other merges are possible. In this case, the feerate diagram remains unchanged, because we end up with the same chunks as before the improvement step, though with a different spanning tree in the re-merged chunk. Whether this can end up in an infinite loop, and if not, how many iterations improving the same chunk this way can happen is an open question.

- If such a self-merge does not happen (because the split-off parent chunk does not depend on the split-off child), imagine that the two new chunks initially take on adjacent positions in the sorted chunk list (which is now no longer properly sorted), where the split chunk used to, with the parent one first. We can look at what happens to the parent and child chunk separately:

- The higher-feerate split-off chunk can in this case only depends on chunks that used to precede it, but it may have a higher feerate than those. The maximum-feerate-difference rule now effectively boils down to this new chunk “bubbling up” (think: bubble sort) until it either ends up in a position where its feerate is no longer higher than what precedes it, or it finds a lower-feerate chunk it depends on, merging with it, and then continuing the process bubbling this merged chunk further up possibly. This is very similar to the behavior inside the post-linearization algorithm described earlier.

- The same process, but reversed, happens to the split-off child. Its feerate dropped compared to the earlier chunk, so now chunks that used to succeed it may now have higher feerate than it. So the split-off child chunk starts bubbling down, until it finds a position in the sort chunk list where it has higher feerate than what follows, or when it encounters a higher-feerate chunk that depends on it, where it merges, and possibly continuing further.

Whenever a self-merge does not happen, every improvement step strictly improves the feerate diagram, by moving a higher-feerate part up, and a lower-feerate part down, each potentially merging with other chunks. So the question of termination is just about improvement steps that result in a self-merge.

2.2.3. Split by maximizing (feeparent sizechild - feechild sizeparent)

It remains to be discussed how to decide what split to perform within an improvement step when there are multiple possible options. If it is the case that every improvement step is guaranteed to make some kind of progress, it may be acceptable to just make improvement steps randomly, but perhaps we can do better.

Going back to the LP formulation of the problem, it is a requirement that the derivative of the goal variable g w.r.t. the variable being made free (in the case of a split, the d_j variable) is positive (this translated to needing a would-be parent chunk to having higher feerate than the child). A natural choice is picking the one with the highest derivative in the simplex phrasing. Working that out corresponds to maximizing the function

for A the would-be parent chunk and B the would-be child chunk. And from casual fuzzing, this indeed appears to be a good choice, with apparently relatively low worst-case numbers of iterations. Furthermore, it appears to result in never repeating the same split (in the sense that the same chunk is never split in the same parent and child chunk, ignoring the exact spanning tree it has. Other rules (e.g. maximizing feerate difference directly when splitting) don’t seem to have this property: while they don’t repeat the exact same state, they do appear to result in sometimes repeating the same splits a finite number of times.

Another insight is that if a split step does not result in a self-merge (see above), q(A,B)/2 is a lower bound on increase in surface area (integral) under the feerate diagram curve, which is directly related to our overall goal (because the optimal linearization necessarily has the highest-possible surface area under the curve).

The q() function has other interesting properties too, which may or may not matter:

- q(A,B) = \sum_{i \in A} \sum_{j \in B} q(i,j) (i.e., it is a bilinear map).

- q(A,B) = q(A, A \cup B) = q(A \cup B, B)

2.3. Initial state

We started with stating that the initial state is all dependencies inactive (i.e., all transactions in their own chunk). But that state is typically not topologically valid, which is a requirement for the analysis of the improvement steps above.

It is possible to just start with a general merging step to avoid this: even just merging everything randomly would suffice. But we can do better. In practice, we always start with a known linearization for a cluster, and the goal is improving it, rather than finding a new linearization from scratch.

With that, we can use the following approach:

- Iterate over all transactions in the input linearization, from front to back. And for each:

- Perform a bubbling-up merge on the chunk that transaction is in (initially a singleton).

The result is actually exactly the post-linearization algorithm, but in the spanning-forest setting. This means that the chunks that come out, even without any further improvement steps, will form a linearization at least as good as the input linearization. Any work done on top just makes it even better.

In other words, we can see this as natural linearization-improvement algorithm, avoiding the need for LIMO or explicit linearization merging. A downside is that it is unclear how to incorporate a “make sure every next chunk is at least as good as the highest-feerate ancestor set among what remains”, without explicitly computing such a linearization and merging with it. It is unclear how big of a problem that is.

2.4. Resulting combined algorithm

Putting all the pieces above together, we get:

- SpanningTreeLinearize(C, L)

- Helper function: MergeUpwards(T)

- Loop:

- Find the chunk H which transaction T is in.

- Among all other chunks H’, which H has an (inactive) dependency on, find the lowest-feerate one.

- If no H’ is found, stop loop.

- Activate a dependency between H and H’.

- Loop:

- Helper function: MergeDownwards(T):

- Loop:

- Find the chunk H which transaction T is in.

- Among all other chunks H’ which have an (inactive) dependency on H, find the highest-feerate one.

- If no H’ is found, stop loop.

- Activate a dependency between H and H’.

- Loop:

- Helper function: Improve(D)

- Deactivate D, resulting in chunks Hp and Hc.

- If Hc has a dependency on Hp, activate it and stop.

- Otherwise:

- MergeUpwards(Hp)

- MergeDownwards(Hc)

- Initialize state with all dependencies of C as inactive.

- For each transaction T in L:

- MergeUpwards(T)

- Loop:

- Among all active dependencies, find D, the one with the highest q = fee(Hp)size(Hc) - fee(Hc)size(Hp), where Hp is the would-be parent chunk if it were deactivated, and Hc the would-be child chunk.

- If q <= 0, or no active dependency exists, stop.

- Improve(D)

- For all chunks H, in decreasing chunk feerate order, tie-breaking by topology:

- Output H in arbitrary topologically-valid order.

- Helper function: MergeUpwards(T)

3. Speculation about complexity

In my prototype implementation, I have used a number of techniques to make this efficient.

The main one is to maintain at all times the precomputed would-be parent chunk fees and sizes for each active dependency. This is fairly expensive, but for each update (merge or split) can be computed at once for the entire chunk at roughly the same cost as would to compute it for just one dependency individually. To update after a merge:

- Let T and B be the top and bottom chunks being merged.

- Travel from the activated dependency outward, along active dependencies, and:

- For each dependency D traversed downwards (reached the parent transaction before the child):

- If D is inside T, add B’s fee/size to D’s would-be-parent fee/size.

- If D is inside B, add T’s fee/size to D’s would-be-parent fee/size.

- For each dependency D traversed downwards (reached the parent transaction before the child):

And similar for splits, except subtracting instead of adding.

This has cost O(d) per update, where d is the number of active and inactive dependencies that are inside or on the border of the chunk. As this may include all dependencies in the graph, d may be up to O(m), but by keeping track within each transaction which dependencies are active and inactive, it may be possible to bring it to O(n) (as at most n-1 dependencies can be active at a given point in time).

Every split step requires looking over all active dependencies, comparing their would-be parent chunk feerate with the would-be child chunk feerate, to determine which to split, which is O(n), as there are at most n-1 active dependencies. Let s be the number of improvement steps performed. The number of splits is of course s: one per improvement. The number of merges may be up to s+n-1, as we can start with up to n chunks, end with at least 1, and each merge reduces the number of chunks by one, while each split increases the number by one. Lastly, each merge is O(m) to figure out what to merge with, but it may be possible to bring this down to O(n) by observing that no two dependencies from the currently-being-bubbled chunk to the same chunk are worth considering. So overall, I believe this leads to a cost of O(m(s+n)), and it may be possible to reduce it to O(n(s+n)) = O(ns + n^2).

The big question is of course what s is. Basic on fuzzing results, it seems to mostly depend on m, and be somewhat super-linear in it, perhaps m^{3/2} or m^2. Given the fact that m may be up to n^2/4 itself, this leads to an overall complexity of maybe (and again, this is just based on very basic fuzzing and extrapolating the worst case numbers seen) of somewhere between O(n^4) and O(n^6). It is also entirely possible that the worst case is exponential and I just haven’t been able to discover the cases that exhibit this behavior, or it may even be the case that non-terminating examples exist.

3.1. Goals

Note however that while the best possible complexity is certainly an interesting research question, what matters practically is rather:

- What is the largest cluster size for which we can guarantee a “good enough” linearization in a very short timeframe (think ~50 µs). So far, we have defined “good enough” as “each chunk is at least as good as the best remaining ancestor set”, as that is both efficient to compute (O(n^2)), and roughly matches the existing CPFP-aware mining algorithm in Bitcoin Core. Since this is a whole-linearization algorithm, and not an individual find-good-subset algorithm, it may be hard to incorporate actual ancestor set finding in it, but maybe an argument can be made that k iterations of spanning-forest improvement steps is qualitatively as good as ancestor set, for some function k.

- Beyond the minimal “good enough” above, I think the real question is which algorithm has the best worst-case “improvement per unit of time”, for cluster sizes within the bound established above.